Archives

That 1970 Joseph Epstein Thing

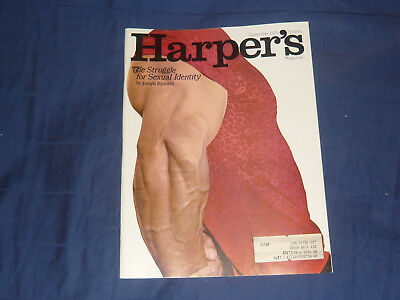

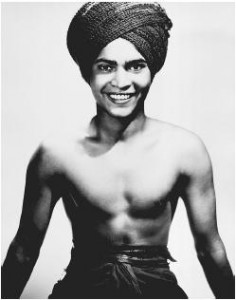

“The cover: The indubitably masculine muscles in the photograph belong to Rick Wayne, editor in chief of the monthly magazine, Muscle Builder Power, and winner of the Mr. World title in 1967.” (Per mudcub site)

Epstein’s article about his fear of homosexuals was recognized as twisted and personal when it was published in Harper’s in 1970. It’s still really weird today, even as a period piece. And yet…and yet…it’s an enjoyable, fascinating romp through the meadows of self-justification.

This text, scraped from a site called mudclub, does not include the piquant photos of a Greenwich Avenue haberdasher’s windows with remarkably epicene mannequins…but perhaps we can find them.

The article is cluttered with unnamed and disguised personalities that must have set many minds to wondering. This mayor of a mid-sized Southern city who makes a pass at Epstein at the country club—who is that, and what’s the city? It appears it was longtime mayor Casey Laman of North Little Rock, Arkansas.

I know this because Epstein provided the key, decades later, in a memoir he wrote for Commentary, “And That’s What I Like About the South.”

Casey is La Man.

That “mid-sized Southern city” description was a real curve-ball. Here I was thinking Huntsville or maybe Shreveport. And he doesn’t mean North Little Rock, but Little Rock, Arkansas itself, where he lived on a couple of occasions, and which he wrote about in his first published article in New Leader in 1959.

Mature Joe

Getting a picture of Epstein himself in the 1960s is not easy. There are plenty of images of old Epstein from the last twenty years, but nothing from his North Little Rock days. One of the amusing ironies of my online hunt for a 1960s Joe Epstein portrait is the search results give you plenty of pictures of one of the most famous homosexuals of the era: the handsome, always nattily attired Brian Epstein.

There are a few typos or misprints in the article reproduced below, probably a result of some mis-scanning or proofing oversight. Addendum Dec 12, 2020: I now have a copy of the original, with typography and graphics, downloadable here: HarpersMagazine-1970-09-0021110

“Homo/Hetero: The Struggle for Sexual Identity”

(Harper’s magazine, September 1970. Blurb: ‘Homosexuality in “swinging” America is very much out in the open. Yet the homosexual’s status is still that of an outlaw, even in a hedonist society that has learned to get its kicks where it can.’)

In the beginning, I felt confusion, revulsion, and fear. I must have been nine or ten years old when my father, who had read me stories out of a children’s Bible, out of Robin Hood, out of the Brothers Grimm, who carefully instructed me never to say the word “nigger”, one night sat me down in our living room to explain that there were “perverts” in the world. These were men with strange appetites, men whose minds were twisted, and I must be on the lookout for them – for myself, but even more for my little brother, who was five years younger than I. There were not many such men in the world, but there were some, and they might wish to “play” with my brother or me in ways that were unnatural. I was being told this so I might know about them, but I must not be afraid. A short while later I went to bed and dreamed about a tall thin man in a floppy black hat, a black cape slung round his shoulders, his face turned away from me, who extended a bony long-nailed index finger out to touch my little brother’s bared genitals. I woke screaming.

Later incidents occurred outside of dreams.

It was the Christmas holidays in Chicago. Through my father I had a job selling costume jewelry in a store on State Street in the Loop. I was sixteen but looked more like twelve; small, slender, clear-skinned without a hint of beard, long eyelashes, and soft, regular features. I was what was then known as a pretty boy. It was four o’ clock in the afternoon, and a man had been standing outside the window of the store staring in at me off and on for several hours. Looking to be in his late forties, of medium height and build, he wore an expensive camel’s hair coat and was in no way effeminate. Over the course of the afternoon, his look changed; sometimes he glowered at me, sometimes he smiled. But his attention was constant, and made me terribly uncomfortable. At five, quitting me, he was, thank God, gone.

The next day he returned. He put in his first appearance outside the window at ten in the morning. He was back at noon. At three he was back again. At four-thirty he smiled and, unmistakably, winked at me. At five he was waiting outside. As I left the store, he fell in step alongside me. I had less than a block to go to the subway.

“Hello there, young man.” His voice was cultivated, very masculine, even fatherly.

“Hi,” I said, relieved that my own voice did not tremble.

“Do you work here regularly?” he asked.

By the time I explained to him that I did not, that I had only been hired to help out during the holiday rush, we were at the entrance to the subway station. I stopped and he, seeing I was about to depart, knew that he had to make his move.

“I’m from out of town,” he said. “I’m staying right here downtown at the Sheraton. Would you care to spend the evening with me?” He paused, then added, “I’d make it worth your while.”

I said his offer was very kind, but that I had left my mother’s car parked near the subway station where I got off, and that I needed to get it home. My politeness only encouraged him.

“What about tomorrow evening, then?”

It was time to use the ammunition I had been saving up.

“It is really nice of you to ask me,” I said, “and I certainly don’t mean to hurt your feelings, but the truth is, next year I intend to begin studying for the priesthood. I hope you understand.”

He accepted this, wished me all good luck, and left. Fishing some change out of my pocket while walking down to the subway, my hand shook badly.

There were other incidents of this kind, but they by no means occurred regularly. Homosexuality during the years I was growing up seemed furtive and in the main rather desperate. Occasionally, the story would go round about a couple of kids who went in for homosexual play of some milder form – at its most extreme, as the story went, this might involve mutual masturbation – but usually this information was sufficient to disqualify them from the set I traveled with. From the age of ten years old on, we were athletes; our calendar was divided into the three major sports seasons. In Chicago in those years – the early and middle Fifties – we could get our driver’s licenses, and these coveted documents set us loose on the great sex hunt. With Chicago machismo, also universal adolescent horniness, we buzzed off in our fathers’ cars for the cathouses of Braidwood and Kankakee, Illinois, or tracked down streetwalkers on the city’s South and West Sides. Once in a while I would hear about four or five guys who had picked up a homosexual. They would let him perform fellatio on each of them in turn, right there in the back seat of the car, and then, without hesitation, beat the living piss out of him.

More commonly, homosexuality seemed an exotic, a flamboyant thing. There was a drag club in Chicago in those years – called, I believe, Club Delilah – which featured female impersonators. It was the sort of place one’s parents might go to on what then passed for an offbeat night out. Such was the public exposure of homosexuality at that time: an entertainment, a freak show for the middle class. Other exposure was at a minimum. There was the infrequent gay bar on Rush Street, more often closed than open, due no doubt to the harassment of the Chicago cops. Sometimes you might see a great swishy colored queen, a traffic stopper, sashaying down the streets of the Loop, or find yourself trough-to-trough in the men’s room of a downtown movie theater with a very suspicious-looking player. But none of this was a regular feature of life. In fact so uncommon a phenomenon did homosexuality seem that I recall it first being discussed in any extensive way in connection with Hollywood. In Hollywood everyone was queer. No one who lived there got off without having the charge leveled at him at one time or another, with the possible exception of Gabby Hayes.

The University of Chicago, where I went to school, was, for its day, as socially avant-garde as any college in America, but homosexuality was not part of the scene there. In a school where Freud’s Civilization and Its Discontents was taught freshman year, heterosexuality brought complications enough. There were vague rumors of certain Byzantine carryings-on in Burton Judson Court, the men’s dormitory, but, as far as I was ever to learn, their factual content was less than clear. Even if true, what was said to be going on, a rare coupling or two, was certainly nothing on a very grand scale.

The Army, too, offered rumors in plenty but again, in my experience, nothing in the way of evidence. “I trust none of you gentlemins will take it into you haids to go crawlin into a buddy’s bunk on any of dese here cold Fort Leonardwood nights, dere,” said First Sergeant Andrew Lester. And I had not heard of anyone who did—not in basic training at Fort Leonard Wood, nor at clerk-typist school at Fort Chafiee, nor during my ten-month stint as crack movie reviewer for the Fort Hood Armored Sentinel.

For the second of my two years in the Army I was transferred to a recruiting station in Little Rock, Arkansas, where I worked a light half-day typing up the results of physical examinations. Good duty this, for Little Rock had no Army base nearby which meant that I, like everyone else attached to the recruiting station, was able to have an apartment of my own in the city. The great socially segregating fact in the Army is not race but education and the only other enlisted man at the recruiting station besides myself who had finished college was a man whom I shall call Richard. He was part Lebanese, from Cleveland, and had taken a degree in landscape architecture just before being drafted.

Richard was stocky, darkly good-looking in a altogether manly way, with strong rough hands, the result, doubtless, of his profession. We would usually have coffee together at work. Our conversation rarely struck the depths; mostly we bitched about the Army and spoke of our longing to be free of it. Once, however, we hit on the subject of family life among ethnic groups, and Richard said that when it came to clannishness the Lebanese beat all hell out of the Jews or for that matter even the Greeks. His mother was not Lebanese, but Irish Catholic and this had been a source, he said, of great pain in his father’s family, who never really accepted him. It had been an important factor in the breakup of his parents’ marriage, for his father, who also had a drinking problem, deserted his mother when Richard was nine years old.

Although I never saw Richard at night or on the weekends, one Saturday morning I ran into him in downtown Little Rock. I was with a girl I had been taking out at the time. Stopping briefly to say hello he seemed vaguely uncomfortable.

“Where do you know him from?” the girl asked after Richard had gone on.

“We work together,” I said; “I don’t see much of him outside of work, but he’s very nice.”

“I suppose you know he’s a roaring fag,” she said. In fact l knew nothing of the kind. She then explained that the weekend before she had gone, at the invitation of a decorator she knew, to a drag ball, where she had seen Richard rather conspicuously necking with another man.

I was stunned, then angry. I was angry, first, at my own lack of judgment and subtlety in not deducing that Richard was a homosexual; and, second, more intensely, at being victimized by his duplicity. We were not close friends, but I liked him, and it now seemed that every moment we had spent together was a huge sham, an elaborate piece of deception to hide the essential, the number one, fact in his life. Of course his duplicity was necessary, I realized that, but I was nevertheless offended. I never mentioned anything about any of this to anyone at the recruiting station, but I never felt quite right about Richard again.

When l went to work in New York, it seemed as if almost everyone I knew was in psychoanalysis, or had just broken away from it, or was about to begin it. This gave conversation a rich, though somewhat narrow, frame of reference. Among these people a waitress need only forget to bring water to the table to be accused of penis envy. The label “queer” was pasted onto people with a casual abandon; sometimes it was used with a true McCarthy-like malice of intent. Once affixed to a man, it was not easily slipped of. But he seems very masculine, I might argue on behalf of someone so accused. “Hell, he’s one of those tough fags,” would be the answer. But he’s married and has three children, I would point out about someone else. “A closet-queer, obviously,” the answer would shoot back. The most devastating accusation of all, though, was that of “latent queer”; it was devastating because finally unarguable—“latently,” what person isn’t anything one chooses to see in him? The gentle person can be seen as latently aggressive, the shy person latently violent, the altruistic person latently a killer. Appearances, to the really practiced hand at this game, had nothing to do with reality, except to serve as a cover for it. Under such ground rules, the All-Pro linebacker with seven children who philandered heavily on the side was the sure latent homosexual.

In the South where, the fates being tricky, I next turned up as director of an anti-poverty program, one sunny weekday afternoon I found myself seated in the dining room of a country club as the guest of the mayor of a middling-size Southern city. We were meeting to discuss something called the Neighborhood Youth Corps, an anti-poverty program that the mayor had already agreed to have his city participate in. Since he was a man impatient of detail, this lunch had been arranged so that I might explain to him what, exactly, was involved. It was not an unpleasant task, since I liked him, and had from the time months before when I first met him.

The mayor was in his late forties, married, with a daughter at the state university. His hair was prematurely white, and had apparently been so for some years. He took care with his clothes, and was usually done up in flannel blazers or seersucker suits, generally worn with subtly elegant foulard neckties. He had a reputation as a terrific screw-off, a good ole boy in the great Southern tradition – as a heavy drinker and, though not a large man, as a brawler. At a mayors’ conference in a Midwestern city a few years before, he was said to have knocked a man through a plate-glass window in a cocktail lounge; they were still billing him for the damages. He kept a police radio in his car and, when the opportunity arose, led his police force on raids of local whorehouses. With great good humor, he told me about some of these raids, and invited me along on the next one.

“A drink before lunch?” he asked. I ordered a Scotch and water. He ordered a martini, which the waiter, an old black man with a limp, pronounced “montoni.” As l diligently attempted to explain the Neighborhood Youth Corps, he kept interrupting to say, “I do believe I’m going to have me another montoni.” For the next two hours the waiter hopped to and from our table. “One Scotch and water, one Montoni – cornin’ up!” I lost track of the number of drinks we put away; Sargent Shriver please forgive me, I also lost track of the Youth Corps.

At one point, I asked him when he was going to run for the U. S. Senate, for it had been rumored for years that that was the direction in which his political ambition lay. He said it wasn’t likely to be soon. I asked why.

“You goddamn well know why,” he said, leaning over to place a confidential hand on my knee.

A few moments later, washing my hands in the men’s room, I saw in the mirror that I had been followed in. I turned from the sink into his embrace. I shall not attempt to describe the roil of emotion churning within me; I hadn’t, in fact, much time to savor it. I shoved him, hard; his back slapped against the tile wall.

“I’m sorry,” l said; “it’s just not the way I go.”

“No hard feelings, I hope,” he said, straightening his tie in the mirror.

“None whatsoever,” I said, failing to add, only very complicated ones.

In the same Southern city, not long after this incident, I was in a bar one evening with my wife, her sister, and Jim, a young homosexual who did artwork and layouts for the newspaper ads of a large local department store. We had started out earlier in the evening from Jim’s apartment, which was done up like some heavy-handed Hollywood director’s notion of queer digs: the walls were painted Chinese red and there was an oversized organ upon which were perched two ridiculous candelabra.

It took only a few drinks for Jim to get high, and, once high, conversationally to take the offensive. Although no one had been talking about homosexuality or homosexuals, at a certain point, ignoring the women and addressing himself directly to me, he said, “You know, we artists do play a larger role in your lives than you might think. We do your wives’ hair, we design your and your wives’ clothes, we decorate your homes, we write many of the books you read and plays you go to, paint most of the pictures that hang on your walls. I wonder if you have ever considered to what extent you live in a world created by us. Perhaps some day you will.”

This was roughly six years ago, and in the intervening time I have decided that Jim deserves high marks for prescience. For without in any way in-tending to hint at anything so grand as a homosexual mafia or Homintern, what appears clear, and has become increasingly so only over the past few years, is that homosexuals have had a larger share in shaping the contour and supplying the texture of contemporary American life than anyone had probably imagined. The subject of homosexuality, in the meantime, has attained a new openness that is without precedent in this country, while homosexuality itself has proved to be more widespread, to be found in both higher and lower places, than previously seemed likely. Despite all this, there is as little honesty of feeling and accuracy of insight and as much confusion about homosexuality and homosexuals as there ever was.

When you’re confused, the whole world seems queer. And so, at various times, it has seemed of late. There have been, as they say, certain revelations. In England it has come out that almost every member of that rarefied and splendid coterie known as Bloomsbury—both men and women—was a homosexual, including, of all people, John Maynard Keynes. In our own rich public life, there was the sad case of Walter Jenkins, whose great scandal now seems merely a soup stain on the greasy overalls of the Johnson Administration. More interesting is the observation of a lady intellectual I know who has remarked how noteworthy it is that Allen Ginsberg, Paul Goodman, and many other principal publicists and polemicists for youth culture in America are homosexuals. That is not simply noteworthy; it is fascinating.

In the arts, where homosexuality has never been uncommon—in discrete but significant instances, as everyone knows, homosexuals have been responsible for some of the most magnificent works we have—it has seemed of recent years not merely commonplace but dominant. Camp, a Susan Sontag production, was in its origin wholly a homosexual phenomenon. Leslie Fiedler, in Love and Death in the American Novel, has instructed us that the great American novelists form one long daisy chain of failed queers while the principal preoccupation of our national literature has been a disguised (but obsessive) homosexuality. As recently as five years ago, Philip Roth wrote an attack on Edward Albee the main argument of which was that homosexual writers ought to stop concealing their true subject —homosexuality—in elaborate and guileful metaphors, and deal with it openly and directly. How quaint that notion seems now! It wasn’t too long afterward, for example, that Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, a book, it will be recalled, about two young men unmistakably portrayed as implicitly homosexual who had committed a monstrous multiple murder, was reviewed by a self-avowedly homosexual critic who remarked that if only Perry and Dick had had the good sense to pop into bed with one another the crime might never have occurred in the first place. In the middle and latter part of the Sixties, the novels and plays of James Baldwin, a writer of major talent, began to mix the themes of blackness and homosexuality till it became somewhat unclear which of the two was really the chief source of Baldwin’s eloquent rage. Elsewhere and everywhere, films, plays, paintings began to crop up bearing a strong homosexual imprint, more often than not unwrapped in guileful metaphor, or for that matter in subtlety of any kind whatsoever.

In the increasingly large sector of American life inhabited by cultural swingers and intellectual fellow travelers, in which a man is esteemed according to the degree of his alienation from his country, homosexuals have become fashionable, in, with-it. In this world where badges are judged wounds, wounds badges, homosexuals have a deservedly high place, for in fact no higher degree of alienation is possible than to be homosexual in an America whose wider majority culture despise: homosexuality without equivocation. There is at most a kind of jealousy of this elite state of alienation, which it might be good to remember mow homosexuals did not choose for themselves to begin with. Thus of one acquaintance, a cultural swinger par excellence, a friend of mine has remarked, “If Jack were a little younger and had it to do all over again, he’d probably turn queer, because he sense that that is where the action is.”

Although a homosexual who lives in a small town, or works at a blue-collar job, or earns his livelihood in and off the straight middle-class world continues to be made to pay the same high psychic price for his homosexuality, in swinging America homosexuality is very much out in the open. “The apparent frequency of homosexuality,” Andre Gide wrote, “depends on how openly it flourishes.” Can there be any doubt that we are in a period in America where it is flourishing very openly indeed? “Mr. Goldberg,” a member of the Gay Liberation Movement recently asked the gubernatorial candidate in Manhattan, “where do you stand on the question of sodomy?”

“I swing from both sides of the bed,” said a man I know in his late twenties, standing tall and prideful in his Edwardian suit and newly liberated skin. A few years ago he had a wife and child; since divorced, he now has a moustache and sideburns. He is totally open about his recent immersion into homosexuality, or, as I suppose he would insist, bisexuality. Would such a man have been so open about his homosexuality ten, even five years ago? It is doubtful. Would he-and here I am speaking without knowing very much about his personal history—even have taken this sort of sexual turn at all? Assuming for the moment that he does not have what the psychiatrists call a strong “homosexual personality structure,” I think this doubtful, too. This is a man who travels with the zeitgeist, in fact rides the express version of it, and in America the zeitgeist has never been more encouraging of hedonism in all its forms, homosexuality among them. One takes one’s kicks where they are to be had. The swinging Sixties offered a large selection. Smoke it, swallow it, eat it, wallow in it, screw it, kick it, stomp it to death, and never mind what “it” is- such appear to be the principal exhortations of the last decade.

In its homosexual strain, this hedonism is best exemplified by something called “the new homosexuality.” It is called that by Esquire, a magazine which I prize for its trendiness, in whose December 1969 issue I first saw mention of it in an article by man named Tom Burke. What is involved, according to Mr. Burke, is that among the young a wholly new conception of homosexuality, and with a new type of homosexual, has evolved in connection with the drug scene and hippie culture generally. Unlike the common stereotype of homosexuals—as portrayed, for example, in The Boys in the Band—as recherché and feminine, “the new homosexual of the Seventies [is] an unfettered, guiltless male child of the new morality in a Zapata moustache and an outlaw hat, who couldn’t care less for Establishment approval, would as soon sleep with boys as girls, and thinks that ‘Over the Rainbow’ is a place to fly on 200 micrograms of lysergic acid diethylamide.” Whereas the “old” homosexuality was more often than not a parody of heterosexual marriage or even heterosexual promiscuity, the “new,” again according to Mr. Burke, is spontaneous (with the aid of drugs), free-wheeling, orgiastic, and frequently bisexual—in a group-grope, apparently, if one sees an open orifice, any open orifice, one fills it. The new homosexuality, in addition, is said to be without trauma and no very big deal “to those who take part in it.” Beauty, and gentleness, and love in homosexual terms used to be essentially feminine,” one of Mr. Burke’s young informants told him. “Now they don’t have a gender.”

I believed what I had read. There was, after all, nothing in the atmosphere to militate against it, and nothing certainly to make one disbelieve it. So I took a random sampling of informed opinion on the question, which means I asked my seventeen-year-old stepson, who has been traveling in hippie circles off and On over the past few years, what he knew about something called the new homosexuality. “If you mean guys buggering one another without much feeling about it,” he said, “it goes on all the time. Drugs don’t necessarily have to be involved. ‘You scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours,’ is the way it’s talked about.”

If this sort of thing is going on, what else might be? One of Mr. Burke’s new homosexuals has offered what he sees as the sexual game plan for the next few decades:

“Once, the good old apple-pie idea was that men and women screwed conventionally in the popular position, or abstained and took cold showers. Separately. Okay, so now ‘normal’ people are finding out that fellatio and cunnilingus are just as ‘normal’ as anything else. So doesn’t it follow that the whole world is readjusting its concept of what is normal and what is perverted—and what is homo or heterosexual? Nobody has to be one thing or the other anymore. Even homos who are still afraid of sex with women—-well, with all these nudes everywhere, how is anybody going to remain very freaked at the sight of anyone else’s privates? I don’t know—bisexual isn’t really a valid word now, because its connotations are old-fashioned. And somebody better come up with the right word, because we’re going to need it. Within ten years, we’ll have she first group marriage. The communes already prophesy it. The population problem will push it along. By 1990, the old husband-and-wife unit will be nearly obsolete. First, there will be trio marriages—though the marriage ceremony will be obsolete, too—in which, say, two guys and a girl live together and all groove on each other with no specific sexual roles. Alter that, group living. Group grooving. It’s coming.”

Is it? Is homosexuality in fact on the increase? Nobody knows for certain, because nobody knows how many homosexuals there are today in America or were at any particular time in our history. In 1918, in what proved to be the most controversial aspect of his famous report, Kinsey claimed that one of every three American men had had an adult homosexual experience. More recently, the Mattachine Society has maintained that there are currently ten million male homosexuals in America, though of course there is ample motive in agitprop for setting the figure as high as possible. But nobody really knows, and for the good reason that there has always been—and for the majority of homosexuals there remains—a need for concealment.

Ignorance about numbers is a sociological shame, really, for in the case of homosexuals an orthodox breakdown of the group into occupations, age levels, and ethnic and religious affiliations could be of enormous aid in helping to understand something of the nature of homosexuality itself. Take, for instance, the Negro. The Moynihan Report has posited that the Negro family has been, in essence, a matriarchy. In the classical, which is to say the Freudian, interpretation, a dominant mother is often cited as the primary cause of homosexuality. Are there proportionately more Negro homosexuals in America than Jewish, or Italian, or Irish, or German ones? There do not appear to be, but if there were, then the classical interpretation would be somewhat vindicated; if we knew for certain that there were not, then we could say with more confidence that homosexuality was caused less by parental patterns than by a class phenomenon. But we do not know.

Still, despite the great ignorance about numbers, current and past, there is good reason to believe that homosexuality is spreading, and will continue to do so. “Rage to your heart’s content! Repress! Oppress! You will never suppress it!” Gide wrote that in 1911. But who today is raging? Who’s repressing? Oppressing? No one I know, and certainly not most of the writers I read. “Where but in the seminaries,” asks Pauline Kael, in the middle of a movie review, “are there still any considerable number of repressed homosexuals?” Statistically this is ridiculous, but there is a truth above statistics, and Miss Kael has seized upon it. This truth is, when it comes to repression, why bother? Especially when so many voices are shouting to go the other way—to let it, as a song of the Sixties has it, all hang out.

To take only a summary count of these voices, there is, to begin on the most esoteric intellectual level, Norman O. Brown, whose work can be—and is—interpreted as an invitation to a polymorphous sexuality. On a less esoteric but wittier level, there is Gore Vidal, a veteran propagandist for homosexuality—more recently, such are the subtle shifts in these matters, bisexuality— who has of late postulated that, the population explosion being what it is, we must turn homosexual or die. Several rungs further down, there is Dr. David Reuben, M.D., author of Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex . . . But Were Afraid to Ask. While Dr. Reuben is contemptuous of homosexuality, viewing it in not very sophisticated terms as a wretched sickness, he shows a generous openness to just about everything else. On television I have heard him say that the only proper opinion about masturbation that “it is the second-best kind of sex.” Dr. Reuben’s book is a best-seller for the very good reason that it tells people precisely what they want to hear. It ought to be entitled Do It! With its repeated emphasis on the brute need for doing it as frequently as possible—in medicine, he has said, there is a saying about the sexual organs: “Those who do not use them, lose them”—Dr. Reuben’s book is hardly likely to escape the notice of a homosexual audience; like the rest of us, they can pick up on any of his several ideas for a healthier sex life and kitchen-test them right there in the home.

Speaking of brute needs, the best intellectual reinforcement for homosexual activity may yet come with the rise of studies in animal behavior. And ethologists are finding that a great range of animals, from insects on up, exhibit homosexuality. To cite but one line in the best straight-man ethological manner: “Sodomy (i.e., anal intercourse) in apes has been noted.” It is sad, but perhaps not altogether surprising, that we have come all the way round to looking to animals for clues to our own behavior. (The better ethologists, incidentally, dis-courage drawing generalizations about human conduct from their findings, but, recalling what has been done in Freud’s name, one can only say, fat chance!) We have so much freedom and so little certainty about what to do with it. We now know so much it is sometimes hard for us not to recognize how little we in fact know. When it comes to homosexuality, we know, or ought to know, that we know next to nothing. I have four sons, and while I do not walk the streets thinking constantly about their sexual development, worrying right on through the night about their turning out homosexual, I have very little idea, apart from supplying them with ample security and affection, about how to prevent it. Uptight? You’re damn right! Given any choice in the matter, I should prefer sons who are heterosexual. My ignorance makes me frightened.

“Homosexuality, also called sexual inversion, is usually defined as the sexual attraction of a person to one of the same sex (from Gr. homo-, `same’; not from Lat. homo, ‘human being,’ ‘man’). This usually, but not necessarily always, leads to various physical activities culminating in orgasm or sexual climax.” That is the Encyclopaedia Britannica speaking, and in the event you are wondering what that “but not necessarily always” is doing in its definition of homosexuality, it is there to show that its author is being responsible. In point of fact, once one gets past the idea of sexual attraction of a person to one of the same sex, all definitions of the homosexual enter into the realm of argument. Is the married man, filled with longing for boys, but stopped by moral compunction or simple social terror from doing anything about it, a homosexual? Are the nonchalant “you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours” kids homosexuals? What place ought to be accorded latency in defining the homosexual? I do not know, nor, apparently, does anyone else. I have heard one bit of wisdom on the subject and it comes not from modern psychiatry but from Norman Mailer. During the question-and-answer session following a reading at Carnegie Hall, Mailer was asked what he thought of homosexuals. A flashy answer was obviously expected. Mailer disappointed. He merely said that he thought that any homosexual who has succeeded in repressing his homosexuality had earned the right not to be called a homosexual.

Perhaps I find myself taken with this remark because it accords so nicely with my own rather blatantly unscientific definition of a homosexual. For me a man is a homosexual who commits physical homosexual acts. I believe that only the man who is physically attracted to other men and acts on his attraction is a homosexual. I almost wrote “deserves to be called a homosexual,” and to have done so would have been more straightforward on my part. “Homosexuality,” William Menninger once noted, “the term itself is almost an anathema.” I do think homosexuality an anathema, and hence homosexuals cursed, and thus the importance, for me if for no one else, of my defining a homosexual as someone who has physical homosexual relations, for it leaves room for my admiration for the man who is pulled toward homosexuality and resists, at what psychic price I cannot hope even to begin to imagine. Men who are defiant about their homosexuality, or claim to have found happiness in it, will, I expect, require neither my admiration nor sympathy.

I HAVE SAID I THINK HOMOSEXUALS CURSED, and I am afraid I mean this quite literally, in the medieval sense of having been struck by an unexplained injury, an extreme piece of evil luck, whose origin is so unclear as to be, finally, a mystery. Although hundreds have tried, no one has really been able to account for it. Freud has given us what has become the dominant model of its origin:

Homosexuality—Recognition of the organic factor in homosexuality does not relieve us of the obligation of studying the psychical processes of its origin. The typical process, already established in innumerable cases, is that a few years after the termination of puberty the young man, who until this time has been strongly fixated to his mother, turns in his course, identifies himself with his mother, and looks about for love-objects in whom be can re-discover himself, and whom he wishes to love as his mother loved him. The characteristic mark of this process is that usually for several years one of the “conditions of love” is that the male object shall be of the same age as he himself was when the change took place. We know of various factors contributing to this result, probably in different degrees. First there is the fixation on the mother, which renders passing on to another woman difficult. The identification with the mother is an outcome of this attachment, and at the same time in a certain sense it enables the son to keep true to her, his first object. Then there is the inclination towards a narcissistic object-choice, which lies in every way nearer and is easier to put into effect than the move towards the other sex. Behind this factor there lies concealed another of quite exceptional strength, or perhaps it coincides with it: the high value set upon the male organ and the inability to tolerate its absence in a love-object. Depreciation of women, and aversion from them, even horror of them, are generally derived from the early discovery that women have no penis. We subsequently discovered, as another powerful motive urging towards the homosexual object-choice, regard for the father or fear of him; for the renunciation of women means that all rivalry with the father (or with all men who may take his place) is avoided….

In “Certain Neurotic Mechanisms in Jealousy, Paranoia, and Homosexuality,” the paper in which the above appears, Freud adds that he has never regarded this analysis of the origin of homosexuality as complete, and indeed then goes on to say that homosexuality can sometimes have its origin in intense feelings against rivals, usually older brothers, sometimes sisters. Since Freud, part of whose genius consisted of knowing precisely where his knowledge ended, a number of other, less meticulously qualified theories of origin have been set forth and an extraordinary load of case studies of homosexuals has been recorded. The overall effect of all this is, to put it softly, daunting, for what emerges is that almost anything can lead to homosexuality. If a dominating mother can do it in some instances, in others so can a disregarding one. If a passive father can do it, so can an overpowering one. A physical deficiency can help bring it about, but then so, too, can great physical beauty, which might achieve the same thing through narcissism. Intense rival feelings or no competitive feelings whatever, too large a penis or too small a penis, walking in on one’s parents making love or having parents who show no affection toward each other—any of these things, or combinations of these things, or combination of combinations could, conceivably, trigger off homosexuality. Read enough case studies and you soon begin to wonder how anyone has achieved heterosexuality at all. Conversely, boys have grown up in families that one might have assumed to supply the most fertile soil for the development of homosexuality—recall our dear friend Alexander Portnoy in this connection—and come out of it robustly, heterosexual. In this sense, the sense of what seems the sheer randomness of its selection, homosexuality seems a curse, a cosmic one, to be sure, but a curse for all that.

But at least two groups would strongly disagree with this notion of homosexuality as a curse: the majority of psychiatrists and psychoanalysts and most homosexuals. “Homosexuality is neither biologically determined, nor incomprehensible ill luck,” the late Dr. Edmund Bergler wrote. Dr. Bergler was an analyst with a special interest in homosexuality, whose practice was said to include a great many wealthy and well-known men, among whom he was supposed to have effected a high number of cures. He located the origin of homosexuality in a psychic masochism developed unconsciously and early in infancy, and, by dealing directly with this psychic masochism which he believed to be at the heart of all homosexuality, spoke with enormous confidence of “an excellent prognosis in psychiatric-psychoanalytic treatment of one to two years’ duration with a minimum of three appointments each week—provided the patient really wishes to change.” Since few men are likely to come forth today to offer the testimony that they are former homosexuals cured by Dr. Bergler, the truth of his claims is not very readily provable.

There is, certainly, room for the amplest doubt. Freud, for one, held out small hope for the cure of homosexuality. He believed that external motives for seeking a cure, such as the social disadvantages and dangers attaching to homosexuality, and other “components of the instinct of self-preservation prove themselves too weak in the struggle against the sexual impulses.” He believed there was hope for cure only where the homosexual fixation had not yet become strongly developed. He felt that almost all homosexuals did not, whatever their protestations to the contrary, really wish to be cured, for they could not finally be convinced that they would find in heterosexuality the pleasure they were asked to renounce in homosexuality. Typically, this included the homosexual who sought help in psychoanalysis. Of such a man. Freud noted: “One then soon discovers his secret plan, namely, to obtain from the striking failure of his attempt the feeling that he had done everything possible against his abnormality, to which he rim now resign himself with an easy conscience.” In the end, Freud believed that to “undertake to convert a fully developed homosexual into a heterosexual is not much more promising than to do the reverse, only that for good practical reasons the latter is never attempted.”

It is not easy to find what, precisely, the psychiatric-psychoanalytic consensus on homosexuality is at the moment. From what I can gather, the vast majority of practitioners appear to believe homosexuality a sickness; and a somewhat smaller majority appear to side with Freud, as opposed to Bergler, on the extremely limited probability of its being cured. Among those who side with Freud, Allen Wheelis, an analyst who is also a gifted writer, has described in what seem to me convincing terms what is involved in achieving a cure:

If a homosexual should set out to become heterosexual, among all that is obscure. two things are clear: he should discontinue homosexual relations, however much tempted he may be to continue on an occasional spontaneous basis, and he should undertake, continue, and maintain heterosexual relations, however little heart he may have for girls, however often he fail, and however inadequate and averse he may find himself to be. He would be well advised in reaching for such a goal to anticipate that success, if it be achieved at all, will require a long time, years not months, that the effort will be painful and humiliating, that he will discover profound currents of feeling which oppose the behavior he now requires of himself, that emerging obstacles will each one seem insuperable, yet each must be thought through, that further insight will be constantly required to inform and sustain his behavior, that sometimes insight will precede and illumine action, and sometimes blind, dogged action must come first, and that even so, with the best of will-and good faith and determination, he still may fail….

Most homosexuals will never have to call on these resources or go through this particular private hell, because most homosexuals, at least officially, look upon their homosexuality as neither a curse nor a sickness and, this being the case, for them the question of cure is mooted. Officially, from the Mattachine Society of New York to Gore Vidal, homosexuality is a preference, like choosing white wine over red, and nothing more. Thus in one of its bulletins, the Mattachine Society notes: “In the absence of valid evidence to the contrary, the Mattachine Society of New York maintains that homosexuality is not a sickness, disturbance, or other pathology in any sense, but is merely a preference, orientation, or propensity.” Gore Vidal would go further, and would have both wines, red and white, brought to his table. Thus in a recent attack on the eminently attackable Dr. Reuben he remarks of “the Dr. Reubens who cannot accept the following simple fact of so many lives (certainly my own) that it is possible to have a mature sexual relationship with a woman on Monday, and a mature sexual relationship with a man on Tuesday, and perhaps on Wednesday have both together (admittedly you have to be in good condition for this).”

In point of fact a great many homosexuals have in the past made similar claims. They have done so, I believe, in many instances for the very good reason that claiming bisexuality seems to enlarge the element of choice, and thus reinforces the notion that homosexuality is indeed a simple matter of preference. To claim less than bisexuality, to admit one is simply and straight out a homosexual is, in the polemics of sexuality, to admit to a limitation, and thereby to a possible wound or sickness.

Only one thing about bisexuality in men is clear, and this is that there are few subjects about which less is known. Psychiatrists and psychoanalysts tend to view it as a state of sexual indeterminacy, and hence of sexual immaturity; Freud, for example, in one of his few remarks on the subject, thought it a way-station through which one must pass on the curative trip from homo- to heterosexuality. Culturally, one gets the sense that in swinging circles there is a tacit sort of approval, even admiration for bisexuality. In swinging terms, after all, it indicates the greatest possible openness to the widest range of pleasure, and any hedonist hero ought, logically, to be equipped for bisexuality.

Whether there is such a thing as authentic bisexuality is unclear; and by authentic I mean a person so sexually constituted as to desire both men and women equally. In all the instances of novels which have bisexual characters, or in other writing by purported bisexual authors, the sexual pendulum almost invariably swings over more emphatically to the male side. The most affecting of Paul Good man’s love poems are those addressed to boys. In James Baldwin’s novels the homosexual relationships are invariably more convincing than the heterosexual ones. In Gore Vidal’s own most recent entry into this field, Two Sisters, his memoir in the form of a novel, a book about Vidal’s love for a sexually mixed set of twins, the female twin is so dimly drawn as almost not to exist.

Early in Corydon, Andre Gide quotes a certain abbé Galiani to the effect that “the important thing is not to be cured, as to learn to live with one’s sickness.” And here we come to another facet of contemporary opinion about homosexuality, which is, in effect, the view that one is what one is; that everyone has problems, and what truly marks a man is not his problems but how he deals with them; that the name of the game is adjustment, or coining to terms with one’s real nature. “True vice,” Santayana wrote in another connection, “is human nature strangled by the suicide of attempting the impossible.”

How reasonable this seems, how realistic, how completely and utterly civilized! Yet in the instance of homosexuality, it is not so easy. An acquaintance of mine in New York, the friend of a friend, felt himself on the edge of suicide. Terrified, he went into psychoanalysis. After five or six months, his analyst, a woman, informed him that she thought the major cause of his unhappiness was that he was sexually riven– a latent homosexuality raging within him was at the heart of all his conflicts. Try it, see how it works out, his analyst advised. He did so, and over the course of the next year entered into several homosexual relationships. Apparently the sex of homosexuality in no way repelled him, but the homosexuals he became involved with did. An intelligent and decent fellow who craved among other things stability in his friendships, he found himself going to bed with men who had greater problems than his own. Under strain of the greatest psychic complications, he attempted to return to the sexually straight world, hut could not bring it off. He subsequently eased back into homosexuality. True, he did not commit suicide, and the decision to surrender himself to his homosexuality may have spared him that. But, neither did he find any measure of happiness or any release from his pain in homosexuality.

Elliot, the hairdresser of a lady friend of mine, claims not merely to have found happiness in his homosexuality, but finds the idea of a life outside of homosexuality beyond his conceiving. He is in his middle twenties, small, with intelligent eyes, and an altogether winning manner. I had met him once before; he was then wearing his hair long. At the lunch at which we had arranged to talk about homosexuality and homosexuals, his head was shaved, for shaved heads were “out,” which in Elliot’s set means “in.” Elliot cares about being ”in,” in his own supersubtle way, and manages to bring it off rather gracefully. His style of dress is deliberately outrageous, but expensively so, and there could not have been less than $400 worth of clothes upon Ins back the day we lunched, not counting rings, bracelets, and cuff links.

Elliot became aware of his own homosexuality early. He “came out,” as he put it, very young. This has made a big difference in his life, he felt, because it enabled him to plan it within the confines of his homosexuality. Elliot is a curious cross between the new and the old homosexual. He lives in a homosexual marriage with an older man, and has for the past eight years: he spoke about this man with affection, reverence, and, finally, love. By prearrangement, he is given a lot of freedom to indulge his rather catholic tastes on the side. These tastes run to a nice truck-driver type, married men who have not had homosex before, an occasional woman, provided she be low-down and sufficiently funky. The element of danger in his homosexual cruising tended to incite his passion; danger, Elliot admitted, could be a groove. He had never been beaten up, but once he had brought a man back to his apartment who tied him up and looted the place.

Whatever its social complications, Elliot said he liked homosexuality for its sexual simplicity. Sex, he felt, was better organized for homosexuals than for heterosexuals; there was, he said, a place where he could find whatever he wanted at the moment. If his mood ran to a leather joint, one was to be had; similarly, a sado-masochist joint; for a quick joust, there were always the baths. Elliot said he did not like a lot of talk leading up to sex: in a homosexual bar, he said, you could walk up to a man and say, “You want to fuck? Let’s go to my place.” Either he does or he doesn’t; there is no crapping around about it. He said there was a fraternal aspect to homosexuality as well. It was like being in the Elks or the Moose; you can go to any strange town and right off find your fraternity brothers. Elliot liked this fraternal sense of the homosexual community, “the secret societyish thing,” as he called it, and said that some of the fun might go out of homosexuality if it were ever to become totally accepted.

At one point, Elliot asked me what I felt about homosexuality for myself. I told him that, sexually, it repelled me. Even had I a desire for a man. I said, I would try my damnedest to fight it off, for knowing something of the mechanisms of my own mind, I know I should probably be made to pay a large measure of guilt and other complicated feelings which I do not now pay in the shabby heterosexual skin I have become rather happily accustomed to. Besides, I said, as long as I didn’t have any desire for a man, I didn’t feel I was missing anything. I did not put that high a premium on experience for its own sake. I am sure, I told him, that a whole cluster of interesting emotions go along with murdering a man, but I was not ready to murder to experience them. Elliot said that if he thought he could get away with it, he would murder for the experience of murdering. He was not being sincere, I thought, but merely callow. Earlier he seemed more in earnest, and more affecting, when he said that he sometimes gave himself to an old man at the baths. “I figure why not,” he said, “someday when I am an aging queer maybe some beautiful young thing like myself” – here he tittered in self-irony – “will give himself to me.”

Homosexual appetites, tastes, and fantasies, one is reminded while listening to Elliot, appear to be every bit as various as heterosexual ones, with the range of homosex—running from an almost Platonic love to sadistic lust—being no less wide than that of heterosex. Now that the notion that heterosexuality is primarily for the purpose of procreation no longer has any real direct force in most people’s lives, heterosex, being officially recognized as an agency of pleasure, has itself taken some very fancy turns. (All those marriage manuals describing all those new positions, tricks, little surprises! ) Certainly, nowadays it is not so easy to say, heterosexually speaking, what is natural and what is not. The only standards left us for determining what is not natural sexually are physical injury and lack of consent—all else, apparently, goes. This being the case, one can’t say with the same old confidence that homosexuality is unnatural, however deeply one might feel that it is. One cannot even any longer say that it is uncustomary—it flourishes openly in America at the moment and, as every semiliterate homosexual will gladly inform you, it also had its day in the ancient world.

Not only does the argument between heterosexuals and homosexuals about what is natural and unnatural seem a stalemate, but of late homosexuals seem to have taken to the attack against heterosexuality as a way of life. “Don’t tell me about the glories and joys of married life,” Elliot says. “I know something about those from the women I work on.” And of course, in a sense, he is right. Heterosexuality has not been without its own special horrors. Over the past few years I have witnessed my own once marvelous marriage crumble, fall, and dissolve into divorce. I look around me and see so few good marriages: I know of so many people of my generation—men and women between thirty and forty—who, if they thought they could bring it off, would not return this evening to the person they are married to. They stay together because children are involved, or they fear the guilt of breaking away, or do not wish to admit failure, or are simply terrified of loneliness. So often so much that is extraneous to love or any other kind of mutual regard binds these marriages. The heterosexual singles’ scene does not hold out greater promise. Frequently, this comes down to little more than the mating of beasts. “Ah,” sighs a friend, about to comment on nearly two decades of bachelor life, “the screwing I get isn’t worth the screwing I get.”

Yet if heterosexual life has come to seem impossibly difficult, homosexual life still seems more nearly impossible. For to be a homosexual is to be hostage to a passion that automatically brings terrible pressures to bear on any man who lives with it: and these pressures, which only a few rare homosexuals are able to rise above with any success, can distort a man, can twist him, and always leave him defined by his sexual condition. The same, I think, cannot be said about heterosexuals. With the possible exception of prostitutes and heterosexuals driven by abnormal appetites, the general run of heterosexuals are not defined by their sexuality at all. Although the power of sex is never to be underrated, in the main for most heterosexuals sex beyond adolescence becomes a secondary matter, a pleasure most of the time, a problem only in its absence. Homosexuality, on the other hand, is a full-time matter, a human status—and that is the tyranny of it.

The homosexual’s status is that of an outlaw and, even if most of us do not customarily think of it that way, most homosexuals know it is true. Homosexuality has in fact formally had an outlaw status in this country for years, and laws against homosexuality, however unevenly enforced, are currently on the books of all but one of the United States. These laws are barbarous, not to say illogical: when committed by consenting adults, homosexuality is a crime without a victim, and for this reason alone the onus of criminality surely ought to be lifted. Perhaps the audacious and unguent Gay Liberation Movement will bring about the abolishment of these laws—and one can only say, more power to them. (Has there, incidentally, ever been a more misplaced epithet than “gay”?) Excepting only child molestation or youth seduction—hetero- as much as homosexual problems—homosexuality is a private matter.

Private, too, are our ultimate reactions to it. For most people these reactions run very deep indeed. Among women who feel strongly about it, reactions seem to fall into one of two categories. Some women, especially those who are confident of their femininity, sensing that homosexuals look upon them as the enemy, tend in turn to look upon homosexuals as the enemy. Other women I know have developed friendships of considerable depth with homosexuals. They claim to find a special sensitivity in these men, a subtle sense of the nuances of feminine feeling that is not available to non-homosexual men. The fact that homosexuals pose no seductive threat to them, nor, as is seldom the case with female friends, offer rivalry on any front, makes, these women claim, for a special sort of wholly noncompetitive relationship that is not to be had elsewhere.

Women also seem by and large better at the game of spotting duplicitous homosexuals. Are they, one wonders, better because in some fundamental way they feel their own sexuality menaced in the presence of a homosexual? Whatever the reason, there is something crazily instinctive and mysterious about it all. Things really start to sound crazy and mysterious when you ask women how they determine if a man is homosexual. “There is something strange about the formation of a homosexual’s mouth and cheeks.” “I look for something in the walk, a certain almost imperceptible sway in the hips.” “I can usually tell a homosexual by the fact that, upon meeting him for the first time, he will generally come up with a remark that is a good deal wittier than a heterosexual man is likely to come up with or is probably even capable of.” If all this sounds a bit nutty, it’s because it is. But then we are all of us a bit nutty on the subject of homosexuality.

It is this persistent nuttiness, which to some extent all of us are prey to, that makes me believe that homosexuality, however openly it is now carried on, however wide the public tolerance for it, is no more acceptable privately than it ever was. Between public tolerance and private acceptance stretches a wide gap, and private acceptance of homosexuality, in my experience, is not to be found, even among the most liberal-minded, sophisticated, and liberated people. Homosexuality may be the one subject left in America about which there is no official hypocrisy. Comedians do homosexual bits with the kind of assured approval from their audiences that they could not hope to achieve with Jewish or Negro bits of similar malice. Nobody says, or at least I have never heard anyone say, “Some of my best friends are homosexuals.” People do say—I say—”fag” and “queer” without hesitation—and these words, no matter who is uttering them, are put-down words, in intent every bit as vicious as “kike” or “nigger.”

I am not about to go into a liberal homily here about the need for private acceptance of homosexuality, because, truth to tell, I have not privately accepted it myself—nor, I suspect am I soon likely to. In my liberal (or Liberal’s) conscience, I prefer to believe that I have never done anything to harm any single homosexual, or in any way added to his pain; and it would be nice if I could get to my grave with this record intact. Yet I do not mistake my tolerance as complete. Although I have had pleasant dealings with homosexuals professionally, also unpleasant ones, I do not have any homosexuals among my close friends. If a close friend were to reveal himself to me as being a homosexual, I am very uncertain what my reaction would be—except to say that it would not be simple. I clearly do not consider a man’s homosexuality, as certain ihomosexuals would argue, merely a matter of sexual preference on his part, something vestigial to him, but instead I think it goes deep within him, that it cannot but have affected him strenuously, making him either a stronger man or a weaker, a better man or a worse—whichever, at all events, an essentially different man than he would be if he were not a For this reason, and from an absolutely personal point of view, I consider it important o know whether a man I am dealing with is a homosexual or nut. Not long ago the BBC did a retrospective on the art of Sergei Diaghilev. Every aspect of Diaghilev’s illustrious career was covered from every possible angle, when the last man to be interviewed for the show, an aged Russian homosexual who was a friend of Diaghilev’s from the 1920s, said: “Ze ting you must remember about Servei vas dat he vas a very aggressive homosexual.” I think anyone who would ignore a fact of this kind in intellectual criticism or in life, is a fool.

If I had the power to do so, I would wish homosexuality off the face of this earth. I would do so because I think that it brings infinitely more pain than pleasure to those who are forced to live with it; because I think there is no resolution for this pain in our lifetime, only, for the overwhelming majority of homosexuals, more pain and various degrees of exacerbating adjustment; and because, wholly selfishly, I find myself completely incapable of coming to turns with it.

Why can’t I come to terms with it? Is it fear of the latent homosexuality in myself, such as is supposed to reside in every man, that makes this impossible? Do I secretly envy homosexuals, not their sexual pleasure, but their evasion of responsibility, for, despite all that I have thought about homosexuality, I am still not clear about whether homosexuals are truly attracted to men or are only running away from women and all that women represent: marriage, family, bringing up children. On those occasional bleak mornings when I should like to drive away from it all, and keep driving, do I hate homosexuals for eluding the weight of my own responsibilities? Do my difficulties go still deeper, are they even more elemental? A lady of my acquaintance, a woman in her forties of considerable sophistication, lives in a building in Chicago in which also live a homosexual couple who have invited her to a number of parties. She, in turn, has invited them to some of hers. Although they fool no one about the exact nature of their sexuality, both men attempt to pass as heterosexual. One of them, thinking he has hit on a successful formula for his duplicity, pretends to get drunk and proceeds to make heavy-handed passes at her female guests. “Why the nerve of that son-of-a-bitch,” she said. “You just know that after putting on that spectacle, the two of them go down to their apartment and fuck the daylights out of each other. I must say I find it appalling.” I must add, I do too. Not the duplicity, but what goes on in that apartment. How middle-class, how irretrievably square, how culture-bound, how unimaginative—I cannot get over the brutally simple fact that two men make love to each other.

They are different front the rest of us. Homosexuals are different, moreover, in a way that cuts deeper than other kinds of human differences—religious, class, racial—in a way that is, somehow, more fundamental. Cursed without clear cause, afflicted without apparent cure, they are an affront to our rationality, living evidence of our despair of ever finding a sensible, an explainable, design to the world. One can tolerate homosexuality, a small enough price to be asked to pay for someone else’s pain, but accepting it, really accepting it, is another thing altogether. I find I can accept it least of all when I look at my children. There is much my four sons can do in their lives that might cause me anguish, that might outrage me, that might make me ashamed of them and of myself as their father. But nothing they could ever do would make me sadder than if any of them were to become homosexual. For then I should know them condemned to a state of permanent niggerdom among men, their lives, whatever adjustment they might make to their condition, to be lived out as part of the pain of the earth.

TIME: Where Young & Rubicam Outdoor Trade Advertising Totally Disappears

A seldom-remembered detail of the commuter-railroad experience back in the 60s is the prevalence of ‘trade advertising.’ These were posters and car-cards and billboards that you passed but barely noticed in the train car and on the platform.

They didn’t advertise a product per se; they advertised advertising space where you could sell your product.

Catching the train in Bronxville or Cos Cob or New Haven you’d see these ads, often mystifying and surrealistic, lining the station platform alongside the enticements to Broadway plays and musicals:

Gilroy IS Here! The Subject Was Roses. Pulitzer Prize Something.

What? You Haven’t Seen Man of La Mancha (“The Impossible Dream”) Even Once?

Now, those theatrical posters were straightforward. They were clearly selling something, and you knew what they were selling. Trade ads were different. Unless you were in the business, you might not know what a trade ad was up to. If it was plugging WNEW Radio, you’d probably vaguely imagine it was instructing you, the innocent commuter, to listen to WNEW Radio . . . when actually it was telling ad buyers to buy time at WNEW Radio.

Now, those theatrical posters were straightforward. They were clearly selling something, and you knew what they were selling. Trade ads were different. Unless you were in the business, you might not know what a trade ad was up to. If it was plugging WNEW Radio, you’d probably vaguely imagine it was instructing you, the innocent commuter, to listen to WNEW Radio . . . when actually it was telling ad buyers to buy time at WNEW Radio.

One baffling but long-lived trade series was a Young & Rubicam campaign for TIME magazine. There might be eight or ten of these in a single location.

Imagine you’re walking down a long station platform or concourse, and every few yards you see a mockup of a Time magazine cover. There’s a stark, simple image, and one short line of copy mentioning a Time advertiser. For example, you might see the arm of a chalk-stripe suit surrounded by Time‘s red-bordered branding, and the copy would go:

TIME

Where Brooks Brothers buttonholes the Madison Ave man.

That example is made up; Brooks Bros. didn’t advertise in Time, and they weren’t featured in this outdoor campaign. The fact is, I can’t remember any specific copy at all from this Y&R trade campaign for Time.

This forgettability was sort of intentional. The agency was trying to get Mr Advertising Man to buy space in Time right now, this week, in 1968 . . . they weren’t hoping consumers would go around mouthing a brilliant tagline for the next fifty years.

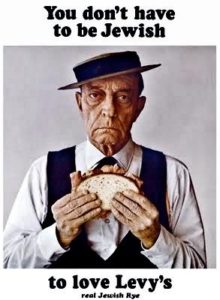

Because that would be tragic. Nothing fails worse than a clever campaign that doesn’t hit the right target. “You don’t have to be Jewish . . . to love Levy’s . . .Real Jewish Rye” is a Y&R line from the era everyone remembers now, though almost no one today eats Levy’s rye bread. I’ve had it recently, so I know it’s still being made.

Because that would be tragic. Nothing fails worse than a clever campaign that doesn’t hit the right target. “You don’t have to be Jewish . . . to love Levy’s . . .Real Jewish Rye” is a Y&R line from the era everyone remembers now, though almost no one today eats Levy’s rye bread. I’ve had it recently, so I know it’s still being made.

I suspect the Levy’s campaign was like the Bob and Ray cartoon ads for Piel’s Beer a decade before. They were popular with young and old, and memorable. But they didn’t move beer sales.

But while we remember the Levy’s ads, the Y&R poster campaign for Time does not stick in the public imagination at all. They have in effect been dropped down the memory hole. I’ve been Googling and otherwise researching Advertising Age and Young & Rubicam histories to see if there’s any mention, any image of the Time campaign. No a chance.

I can’t even find online photographs of station platforms where these ads appeared. I guess no amateur archivist ever thought to snap them. It’s almost impossible even to find photos of Broadway posters online. That’s why I show a Playbill above instead of the actual 1964 theatrical poster for The Subject Was Roses.

can’t even find online photographs of station platforms where these ads appeared. I guess no amateur archivist ever thought to snap them. It’s almost impossible even to find photos of Broadway posters online. That’s why I show a Playbill above instead of the actual 1964 theatrical poster for The Subject Was Roses.

What does stick in my recollection is that the Time campaign was resolutely upscale. A place to advertise quality products for quality readers. That was the subtext.

This all seems laughable today, when Time is popularly reputed to have been a middlebrow book, and now survives in a scrawny print edition filled with ugly pharma advertising and is subscribed to mostly by 85-year-olds, mainly because they got in the habit of reading it around 1957, back when Time ran real news and half its display ads were for gin and scotch.

It’s a repellent little rag now, but in advertising demographics Time was the class act for decades, far outshining the ad-stuffed Life and Look, which were perceived as picture books that subscribers thumbed through. Readers read Time. Readers read the ads in Time.

Trade campaigns for other magazines imitated the Time model to a certain extent—e.g., the endless variants of “Forbes: Capitalist Tool,” which made a subtle pitch to the advertisers by flattering the readers. This series, which ran in and around commuter trains in the 1970s and 80s, looked vaguely like a subscription promotion aimed at ambitious young commuters.

Trade campaigns for other magazines imitated the Time model to a certain extent—e.g., the endless variants of “Forbes: Capitalist Tool,” which made a subtle pitch to the advertisers by flattering the readers. This series, which ran in and around commuter trains in the 1970s and 80s, looked vaguely like a subscription promotion aimed at ambitious young commuters.

But of course the ads were reminding posh advertisers on the train that if they bought space in Forbes they could reach those ambitious young commuters. The kind of people who would read Forbes do not need a train poster to tell them to read Forbes.

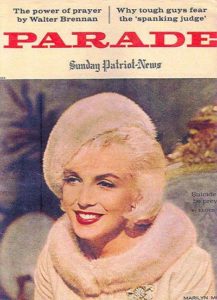

The Sunday Giant

The most pervasive and long-lived of the trade-ad campaigns was probably for the downscale, big-circulation Sunday supplement called Parade. “Parade is the Sunday Giant!” went the slogan, generally on a poster or car-card showing a line-drawing cartoon of a towering figure looming over lilliputian newspaper supplements (New York Times Magazine, perhaps?).

Having mass nationwide circulation was and still Parade’s only real selling point. But advertisers needed to be reminded of this because Parade was easy to overlook. It was and is a one-of-a-kind publication: a bland, friendly downmarket supplement, with content kept so generic it can never seem out of place in Salt Lake City, Sarasota, or St. Louis. This is a difficult trick, and Parade’s done it for, whatever, 70 years? (Look it up!)

Having mass nationwide circulation was and still Parade’s only real selling point. But advertisers needed to be reminded of this because Parade was easy to overlook. It was and is a one-of-a-kind publication: a bland, friendly downmarket supplement, with content kept so generic it can never seem out of place in Salt Lake City, Sarasota, or St. Louis. This is a difficult trick, and Parade’s done it for, whatever, 70 years? (Look it up!)

Back in the 60s and 70s, every town worth mentioning had at least a couple of big Sunday newspapers, and one of them—generally the one with the better funnies and the shorter editorials—carried Parade. In such locales you’d actually see people in stores and newsstands on weekends, thumbing through the hefty Sunday paper to make sure the sports section and Parade were there! The same way parishioners of St. Catherine of Siena in Greenwich might head for the newsstand after Mass, full of beady-eyed intent to ensure that their Herald-Tribune or New York Times wasn’t missing its Book Review section.

P arade emphasized its mass-market, downscale orientation in a dozen ways. In the 50s and 60s, when newspapers boasted of their sturdy newsprint stock and excellent rotogravure processes, Parade went in the other direction and made itself as shoddy as it possibly could. Tabloid-sized and unstapled, its pages were all different sizes, some with rag edges, others cut sharp or with extra dog-ear flaps at the corner. Even on the cover, their color printing was often out of registration, like a 3-D comic book.

arade emphasized its mass-market, downscale orientation in a dozen ways. In the 50s and 60s, when newspapers boasted of their sturdy newsprint stock and excellent rotogravure processes, Parade went in the other direction and made itself as shoddy as it possibly could. Tabloid-sized and unstapled, its pages were all different sizes, some with rag edges, others cut sharp or with extra dog-ear flaps at the corner. Even on the cover, their color printing was often out of registration, like a 3-D comic book.

Parade left a spot on its nameplate where the local newspaper could print its name or logo, and this just added to the cheap feel: the newspaper’s name was often printed crooked or looked like a rubber stamp.

The editorial matter was mostly filler, dealing with celebrities and fads, the sort of stuff you’d see in a popular Hearst newspaper from the 1920s to 1960s. Advice columns and celebrity gossip figured large. The writing went easily: the words weren’t too big, and the sentences weren’t too long, and the attitude was relentlessly chipper.

The main rule seemed to be that if you mentioned a celebrity, it had to be someone recognizable to 95% of the readership. That was the secret of “Walter Scott’s Personality Parade,” an inside-cover feature that started around 1971 and still runs today, although Walter Scott himself has no more corporeal reality than Betty Crocker.

The Walter Scott column was a brilliant addition to Parade, because it ensured that there would be at least one feature that everyone would read. It’s still the first thing you see on the inside: pithy queries and answers about stars and politicians that everybody’s heard of, usually with very upbeat, anodyne answers.

The Walter Scott column was a brilliant addition to Parade, because it ensured that there would be at least one feature that everyone would read. It’s still the first thing you see on the inside: pithy queries and answers about stars and politicians that everybody’s heard of, usually with very upbeat, anodyne answers.

One I remember from circa 1974: “Does Elton John always wear a hat because he’s ‘bisexual’? No, actually he just likes hats! Also he’s having hair transplants!”

Parade’s advertising mechanism I never figured out. Its low-budget, rec-room-floor style could never have been a good fit for most advertisers. (Toothpaste, yes; Tanqueray, no.) Since the same edition was distributed across the country, there was no way it could pick up lavish display ads from retailers or car dealers. Parade survived on cheap ‘n’ cheerful national ads for five-dollar muumuus and anti-itch powder for dogs.

Their perennial full-page advertisers mostly sold stuff you might never see advertised anywhere else, or at least outside a Sunday supplement. There was Zoysia grass, a magical kind of turf that evidently never needed watering or weeding. And there was a weight-loss candy that had the merry name of Ayds. The latter’s ads were always disguised to look like editorial matter, with a first-person narrative, “As told to Ruth L. McCarthy,” related by a former fat-lady.

Their perennial full-page advertisers mostly sold stuff you might never see advertised anywhere else, or at least outside a Sunday supplement. There was Zoysia grass, a magical kind of turf that evidently never needed watering or weeding. And there was a weight-loss candy that had the merry name of Ayds. The latter’s ads were always disguised to look like editorial matter, with a first-person narrative, “As told to Ruth L. McCarthy,” related by a former fat-lady.

(Rumors flew that Ayds contained dexedrine or methamphetamine, but that alas was never the case, and it’s a marvel that the product survived as long as it did. In the 1980s it lost half its business, reportedly because potential customers were scared off by a name that sounded like a killer virus. The manufacturer tried changing the name to Diet Ayds, but that didn’t seem to help.)

One hears sometimes that Parade is a family-run, closely held, business. I find that easy to believe. There’s just enough work here, and just enough money, to support one extended family.

The United States of America School of Writing

I was sketching out a piece on Orwell in the 1930s, and how he had to get along with the Commies to preserve his literary viability. So he posed as a man of the Left without quite being a full Fellow Traveler to the Reds. This took some ruses and finesse. When he went to fight in Spain he joined one of most obscure, ill-equipped factions fighting for the “Republican” side.

Hardie

That was the POUM, an affiliate of the Independent Labour Party in Britain (and another low-efficacy operation, although one of its founders had been Keir Hardie, and such luminaries as Aneurin Bevan had belonged). POUM and ILP were known in those as “anarcho-syndicalist” in orientation. That is, eccentrically leftist. They provided a refuge for people like Orwell who didn’t like the Stalinists but didn’t wish to be in open opposition to them.

Bishop

While batting these ideas around, I recalled a piece that I read in The New Yorker years ago, a very funny memoir by the (now late) poet Elizabeth Bishop. After Vassar, in the early 30s, she worked for some low-rent “literary” operation (actually a writing school) near Columbus Circle.