Here we have the Wyoming Apartments at 853 Seventh Avenue, on the southeast corner of West 55th Street. The Wyoming is a vast old complex, rich in history: the largest residential building in the neighborhood when it was built about 1906. Or rather re-built. It replaced a smaller Wyoming that had been designed a quarter-century earlier by Henry Janeway Hardenbergh, the same architects who designed the Dakota and the Plaza Hotel.

Here we have the Wyoming Apartments at 853 Seventh Avenue, on the southeast corner of West 55th Street. The Wyoming is a vast old complex, rich in history: the largest residential building in the neighborhood when it was built about 1906. Or rather re-built. It replaced a smaller Wyoming that had been designed a quarter-century earlier by Henry Janeway Hardenbergh, the same architects who designed the Dakota and the Plaza Hotel.

This newer Wyoming (by Rouse and Sloan) put all its ornamentation at the top, where it is now virtually undetectable. Thanks to the clutter of delis and electronics shops at street level, passers-by see nothing but an unnamed, undistinguished grey hulk.

Cousin Oswald in his usual habitat: aboard an ocean liner.

I wouldn’t even know it was called the Wyoming if I hadn’t discovered that some remote cousins of mine were living at that address about a hundred years ago. This was the family of a prominent medical pioneer by the name of Oswald Swinney Lowsley, M.D.

Lowsley was a native of Santa Barbara, California, born in 1883. He worked his way through Stanford, taught physical education for a couple of years in Los Angeles, and then entered medical school at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. By age 30 he was urological surgeon at New York Hospital, and at 33 he was named the first head of the new James Buchanan Brady Urological Center. (“Diamond Jim” Brady had earlier endowed a similar clinic down at Johns Hopkins.)

Lowsley lived in the Wyoming, with his young wife, the former Kitty Staples (my great-grand-aunt’s niece, or something like that), and their baby girl; with a baby boy soon on his way.

Doctor Lowsley’s specialty was male urology, particularly diseases and surgery of the prostate. He wrote the authoritative medical texts, he designed the tools (his prostatic retractor is still a hot item), and he largely defined the surgical techniques that would be used for decades to come. And he was familiar with the risks of prostate surgery, which brings us to his second area of specialization.

Amazing breakthrough by surgical savant!

Eldiva, the governess.

Lowlsey developed surgical techniques to cure impotence. Tighten this muscle, shorten that vein—voilà, Uncle Pennybags, you are the Casanova once again! Tactfully described in the press as “rejuvenating operations” to restore “male virility,” these techniques were front-page news in the 1930s.

Another topic that put this eminent surgeon on the front pages was his propensity to remarry. It didn’t seem likely in the early days, when he was a studious, sedate, rather plump young surgeon with a disgusting medical specialty. But then in 1920 he got an appointment as chief surgeon at the American Hospital in Paris. So off to France sailed Dr. and Mrs. Lowsley and their two tots, and their newly hired governess, Eldiva Brown, a Vermont girl with better-than-passable French.

The governess was beguiling; the Lowsleys were soon divorced. Oswald married Eldiva, while Kitty immediately married another physician, a family friend who worked for Esso.

Winifred, the Last Nurse

Oswald and Eldiva stayed married for a good quarter-century, rearing two more children, and figuring prominently in the New York society columns. Lowsley kept up a convivial life on his own, but he kept it out of the newspapers and Eldiva tolerated it all. At least till 1949, when their kids were grown, and she went off to Reno for a fat divorce settlement.

The 65-year-old Dr. Lowsley now married his latest inamorata, a 44-year-old New Jersey divorcée named Celeste Nocito Little. But Celeste did not thrive. She died about a year later, of undisclosed causes.

At the beginning of 1953 Lowsley took his final bride, an Albany nurse named Winifred Atherton, thirty years his junior. They had a six-week honeymoon, after which they traveled some more. In fact they traveled for most of their marriage, which ended two years later when Dr. Lowsley finally died, age 72. Winifred lived on until 1992, outliving not only her husband but all three of his previous wives.

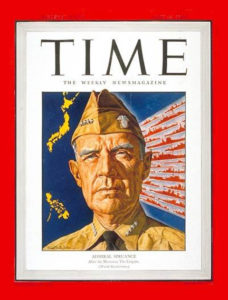

I happened to notice that Admiral Raymond Ames Spruance (1886-1969), perhaps the most effective American naval commander during the war in the Pacific, 1942-44, was born in Baltimore and that his mother’s family name was Hiss.

I happened to notice that Admiral Raymond Ames Spruance (1886-1969), perhaps the most effective American naval commander during the war in the Pacific, 1942-44, was born in Baltimore and that his mother’s family name was Hiss. The Hisses were a fecund clan, and Hiss is a common name around Baltimore. It is possible, even probable, that Raymond Spruance and Alger Hiss were completely unaware of the family connection.

The Hisses were a fecund clan, and Hiss is a common name around Baltimore. It is possible, even probable, that Raymond Spruance and Alger Hiss were completely unaware of the family connection. Here we have the Wyoming Apartments at 853 Seventh Avenue, on the southeast corner of West 55th Street. The Wyoming is a vast old complex, rich in history: the largest residential building in the neighborhood when it was built about 1906. Or rather re-built. It replaced a smaller Wyoming that had been designed a quarter-century earlier by Henry Janeway Hardenbergh, the same architects who designed the Dakota and the Plaza Hotel.

Here we have the Wyoming Apartments at 853 Seventh Avenue, on the southeast corner of West 55th Street. The Wyoming is a vast old complex, rich in history: the largest residential building in the neighborhood when it was built about 1906. Or rather re-built. It replaced a smaller Wyoming that had been designed a quarter-century earlier by Henry Janeway Hardenbergh, the same architects who designed the Dakota and the Plaza Hotel.