(Original version of a piece that has since been published elsewhere. As predicted, the subject died a year or two later.)

One of these days Harper Lee is going to kick off and have great big posthumous laugh at our expense. Bwah-hah-hah! Because right there in her Last Notes and Testament, we will find an answer to that puzzlement that has troubled the publishing biz for a half-century or more.

Namely, why didn’t Harper Lee write any more novels after To Kill a Mockingbird?

And the main reason she didn’t, she will aver in words that are coarse and pithy, is that To Kill a Mockingbird was a phoney-baloney contrived piece of fluff. It wasn’t her novel anymore, not after her agent and editors got through tarting it up, to make it modern and popular and sellable. They mutilated her baby, and young Nelle Harper Lee didn’t have the heart to go through that again.

And the main reason she didn’t, she will aver in words that are coarse and pithy, is that To Kill a Mockingbird was a phoney-baloney contrived piece of fluff. It wasn’t her novel anymore, not after her agent and editors got through tarting it up, to make it modern and popular and sellable. They mutilated her baby, and young Nelle Harper Lee didn’t have the heart to go through that again.

Popular and sellable it certainly was. It was on the bestseller list for about two years, and thanks to the sponsorship of Gregory Peck it became a guaranteed hit movie even before a screenplay was written.

And it was modern. By laying on themes of racial strife and civil rights, and deleting most references to Thirties pop-culture, the publishers made the novel as up-to-date and relevant as the latest issue of Look magazine. The book contains some vague references to the New Deal, and a courtroom trial is said to be happening in 1935; officially we’re in the mid-30s for most of the action. But otherwise the setting might as well be the Deep South of the 1950s and even 60s.

It’s a very peculiar 1930s Alabama that the author conjures up. She doesn’t tell us about seeing Popeye or Shirley Temple or Clark Gable down at the picture show, or reading Beatrice Fairfax or Fontaine Fox in the Mobile Register. In fact, no news at all leaks in from the outside world via radio, cinema, magazines or newspapers. Not a word of Huey Long, the Dust Bowl, Dillinger, League of Nations, Abyssinia, Spain. We are told that our narrator, “Scout,” has been reading since infancy, but she doesn’t seem to read much, not even the Time magazine that her family supposedly gets. International events intrude exactly once, in a painful, smarmy passage in which Scout’s third-grade teacher lectures the class about—what do you suppose? Hitler and the Jews! (Perhaps the teacher does read Time.)

It’s a very peculiar 1930s Alabama that the author conjures up. She doesn’t tell us about seeing Popeye or Shirley Temple or Clark Gable down at the picture show, or reading Beatrice Fairfax or Fontaine Fox in the Mobile Register. In fact, no news at all leaks in from the outside world via radio, cinema, magazines or newspapers. Not a word of Huey Long, the Dust Bowl, Dillinger, League of Nations, Abyssinia, Spain. We are told that our narrator, “Scout,” has been reading since infancy, but she doesn’t seem to read much, not even the Time magazine that her family supposedly gets. International events intrude exactly once, in a painful, smarmy passage in which Scout’s third-grade teacher lectures the class about—what do you suppose? Hitler and the Jews! (Perhaps the teacher does read Time.)

The published novel is very different from Lee’s original typescript. That was a set of loosely linked stories about long summers and oddball neighbors in small-town Alabama. Many of these episodes and character studies are retained in the final product, and they are small, perfect jewels—Boo Radley, the mad recluse; Dill, the narcissistic “pocket Merlin”; Mrs. Dubose, the raging, morphine-addicted Civil War widow; Scout’s snobbish, self-centered cousins who live down on Finch’s Landing.

The novel anticipated the media depiction of the Deep South in the 1960s, and very likely influenced it. Above, the iconic photograph of Sheriff Rainey of Neshoba County, Mississippi, from a December 1964 issue of Life.

This authentic nostalgia is the To Kill a Mockingbird that people fell in love with. However, while these tales still occupy two-thirds of the published book, none of them had sufficient drive or development to carry a major plot. And they were not quite serious, grown-up fiction. “I think for a child’s book it does all right,” Flannery O’Connor wrote a friend around the time the novel won the Pulitzer Prize. And indeed it always has been basically a kiddie story, except for one racy subplot that Lee’s editors grafted onto it. That is the interracial-rape case that dominates much of the second half of the book. Curiously, people who never read the novel, or who mainly remember the Gregory Peck movie, often imagine that this criminal case is the central story, even though it takes up little more than a quarter of the book. (Note: In my HarperPerennial paperback edition of 323 pages, the trial and related events begin at page 164 and end on 259.)

The rape plot is hokum, but the editors and agent who forced it upon Lee knew what they were doing: it ties together many of Lee’s plot strands and characters, and it bumps her wistful recollections up to the grown-up shelf, repositioning it as middlebrow fiction with contemporary (1960) social relevance.

Tastes change. Today the rape plot is laughable, mawkish, stuffed with symbolism. The accused negro, Tom Robinson, has a withered right arm that got mangled years ago when it got caught in a cotton gin. The rapee, Miss Mayella Ewell, comes from a family who are not merely poor white trash from the wrong edge of town, they seem to be illiterate as well. Her father is a murderous drunk, possibly incestuous, who survives by poaching. Her brother Burris is crawling with lice. They are so awful, the story tips over into kind of Tobacco Road black-comedy whenever a Ewell appears. (Thankfully Mayella does not have a harelip.)

Who was the real Tom Robinson? There is a notion prevalent among some schoolteachers and media writers that the Tom Robinson case was loosely based on similar cases in the Deep South during the 1930s. This stems from the vague impression that thousands, or at least hundreds, of innocent negroes were prosecuted and lynched during this era because of White Supremacism and the Ku Klux Klan, and all that nasty bother. According to this school of thinking, Tom Robinson is a composite victim of race prejudice.

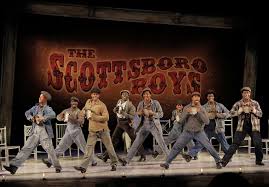

In reality there were very few cases like this. The only notable one in the Deep South that involved interracial fornication with a member of the po-white-trash set was the so-called Scottsboro Boys case. In this saga, we have two young white women who get caught riding railroad boxcars while dressed in overalls. They tell the police they were raped by a gang of black youths also aboard the train. In a protracted series of trials, several of the black youths are convicted of rape and sentenced to long prison terms.

The case was highly publicized in the 1930s, and has never faded from media consciousness, providing fodder in recent years for books, documentaries, and even a Broadway musical. Today the Scottsboro Boys are often spoken of as innocents, martyrs to bigotry and the backward, violent South. The story is put about that the two young women were not only low-class, they were casual prostitutes, and probably deserved what they got, if they really were gang-raped; and anyway, their word shouldn’t be trusted. It’s all their fault.

Scottsboro is frequently cited as the basic template for the rape case in To Kill a Mockingbird. But the resemblance is superficial at best. None of the Scottsboro Boys were hardworking, crippled, husband-and-fathers. In TKAM, nobody suggests Miss Mayella Ewell is a prostitute, or that she deserves to be sexually abused.

The Emmett Till Era. If he wasn’t a Scottsboro Boy, who else could Tom Robinson be? How’s about Emmett Till? This is a theory that scholar-critic Patrick Chura came up with in his penetrating analysis of the novel (Southern Literary Journal, Spring 2000). Chura began by pointing out that the novel has a poor grasp on Thirties history. The WPA shows up two years before the agency was created. And the book’s social attitudes don’t reflect the 1930s at all, rather they seem to echo preoccupations of the 1950s.

Chura rejects the whole Scottsboro theory and says the real prototype for the TKAM rape case was the story of Emmett Till. Emmett Till was a husky, 14-going-on-15 black youth from Chicago who went down to visit his cousins in rural Mississippi in 1955. He made a sexual approach to the young white proprietess of a country store. A couple of nights afterwards Till was beaten to death by the woman’s husband and brother-in-law because he wouldn’t apologize for his behavior.

Chura finds some minor parallels between the two cases. Robinson and Till are both slightly disabled (a withered arm, a stutter), the poor whites are first championed by neighbors, then ostracized because of shame and notoriety. And the trial judges and the press clearly sympathize with the cause of the unfortunate negroes. But the argument doesn’t quite make it. The comparisons are just too strained. Having a stutter is not comparable to having a mangled, useless arm. And the basic narrative of Till case is just too different from the novel’s. The novel’s Tom Robinson is passive and meek. Emmett Till was a big-boy showoff from Chicago who went around bragging that he had a white girlfriend. Even his Mississippi cousins thought he was obnoxious and hoped for his comeuppance.

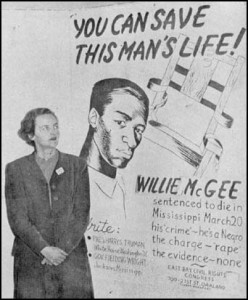

Nevertheless Chura correctly nails the 1950s Zeitgeist of the novel. So it is most peculiar that he overlooks the most notable inter-race rape case of the era, that of Willie McGee. As a news story this went on for ten years (1945-1955). It got headlines, was a leftist and Civil Rights rallying point, and it closely parallels the rape story in To Kill a Mockingbird.

Jessica Mitford and poster, during the CPUSA campaign to protest McGee’s execution. “His ‘crime’ — he’s a Negro.” This sloganeering found echoes in the published version of To Kill a Mockingbird.

Me and Willie McGee. McGee was a black man convicted of raping a (young, attractive, middle-class) white woman in Mississippi in 1945. His lawyers repeatedly appealed, and the appeals were shot down. The case reached a crescendo around 1950, when McGee was due for the electric chair. After a postponement, he was finally executed in May 1951.

The Willie McGee case was a pet cause of the Communist Party USA, through a front organization called the Civil Rights Congress. Now, the CPUSA had been taking a real public-relations beating since about 1945, thanks to Soviet atrocities, the enslavement of eastern Europe, the loss of China, the Alger Hiss case, etc., etc. So now the Party was trying to reposition itself as a kind of charitable, public-spirited organization: a progressive force in favor of Civil Rights and Justice for the Negro. And Willie McGee was an ideal poster child.

In early 1951, as the execution date grew nearer, the Communists came up with a clever retelling of the McGee tale. It was not a simple interracial rape case, they claimed. Willie did not rape that white woman, Mrs. Willette Hawkins; actually Mrs. Hawkins and McGee had been lovers for years! Then Willie wanted to break it off, so the white woman shouted rape to punish him.

Thus sprach the Daily Worker, the CPUSA newspaper. It was a pretty dubious tale to begin with. The McGee case had been going through appeals for five years, yet somehow no one had ever mentioned this long-term “romance” before. But McGee’s new defense team had a wonderfully daffy explanation for this omission: it seems Willie’s original lawyers kept the affair hidden because they thought it would hurt the case, this being Mississippi. (Those all-white juries, you know, with their prejudiced attitudes and all: they might give our Willie something even worse than the electric chair!)

The Party even trotted out a colored woman named Rosalee to tour the country in their dog-and-pony show, telling the world that she was Willie McGee’s wife (she wasn’t) and denouncing Mrs. Hawkins as the white-trash slattern who “raped my husband.”

The Daily Worker kept burnishing its fictional tale of Willie’s romantic entanglement even after he went to the chair. By this point Mrs. Hawkins had heard about it and sued for libel. Finally, in 1955, the Commies admitted they had no evidence. They’d made the whole thing up. The Daily Worker printed retractions and paid a small award for damages.

By that point the Party didn’t care. Willie McGee was long dead, and the story had served its purpose. It had made Willie into a martyr to race prejudice (something we must fight, comrade). Long after most people forgot the details of the case, they’d remember vaguely that Willie McGee was possibly innocent, and executed in a legal lynching.

Because that’s how propaganda works. People don’t remember the logical integrity of arguments. What lingers is the emotional impression. It didn’t matter in the long run whether Willie McGee was guilty or innocent, so long as those “progressive” people who fought for him (e.g., future Congresswoman Bella Abzug) appeared to be on the side of truth and justice.

And there you have it. The tale of Willie McGee, as told in the Daily Worker, was the template for Tom Robinson.

A Parthian Shot. Now, this brings us to Harper Lee’s other big secret about To Kill a Mockingbird. Besides asking why she didn’t write another novel, people routinely asked her which particular racial case of the Deep South she based her rape case upon. She gave vague, dismissive answers, implying that it was a composite of several cases. She never identified any specific case, and no one ever thought to ask her about Willie McGee. After all, McGee was from the 1940s and 50s, not 30s; and anyway, McGee was probably guilty. Therefore, so was the fictional Tom.

And there are even worse complications. If you say Tom Robinson is guilty, then that wise paterfamilias Atticus Finch emerges as one very sleazy lawyer. He does not merely provide competent defense for Tom Robinson, he gratuitously defames the poor girl Mayella Ewell. With no real evidence at hand, he weaves a tale in which she lusted after a crippled black man, and seduced him into fornication. It’s a hair-raising, lurid tale, but it is completely unnecessary. As a fictional device it symbolically shifts the guilt from Tom Robinson to Mayella, but it adds nothing to Tom’s defense case. The jury and townspeople are not really concerned with the issue of consensual vs forcible sex, or whether this person lusted after that one. The two givens in the case are that penetration took place, and that it was interracial. For the men in the jury box, that last bit is the real offense.

Atticus knows they’re not going to acquit his client, so he makes up an unpleasant tale about Mayella, all the while feigning pity for the pathetic lass. But it’s all invention and false sentiment, just like the fantasies that the Daily Worker conjured up about Willette Hawkins and Willie McGee.

Notes and References:

Patrick Chura compares novel to the Emmett Till saga in the Southern Literary Journal.

Alex Heard, author of The Eyes of Willie McGee, blogs about the McGee case.

Washington Post review 2010.

Notes on Bella Abzug and the Civil Rights Congress.

Mockingbird: A Portrait of Harper Lee, by Charles J. Shields, 2006, is particularly good on the shaping of the TKAM phenomenon, both book and movie.