I was happy to go to work for Wine & Dine a few years ago, because I had a long history with its parent company, and it seemed to be a cheerful place. Pretty girls in pretty dresses with cute shoes and nice pedicures. Just what I wanted to be a few years back (before I got old and bitter).

Best of all, it was only twelve blocks from my back door. Theoretically I could travel door-to-door in ten minutes without breaking a sweat, so long as there was no traffic and the sidewalks were empty. Theoretically, I say; as my neighborhood is perennially clogged with taxis, tourists, and worker-bees, the march often took a long and painful twenty minutes.

Eventually I detested this walk—with its crowds and crosswalks and the amputee beggars who congregated on 6th Avenue between 46th and 47th Streets—and deeply regretted having chosen this job over the one that paid 25% more but was out of town. I hated the job too, as the months went by and I faced up to the fact that I was overworked, underpaid, chronically ill with stress-related health problems. There was also the dawning realization that my coworkers were very very stupid. But this took a while to hit me.

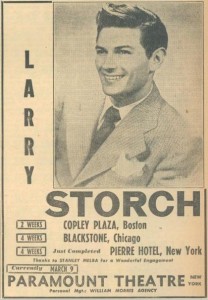

Bobbysoxers’ delight! Larry at the Paramount.

Ignorance Is Bliss. One day I was waiting for the light to change near Radio City Music Hall, and took note of the ancient, frail man beside me. He was 80 years old or beyond, and carrying a saxophone in a bag. The bag had a tag: LARRY STORCH, with Mr. Storch’s phone number. I struck up a conversation. I told him how much I loved his role as Corporal Agarn in F Troop and his cameo as a crazy guru in some Blake Edwards comedy. He was charmed—amazed, really—that anyone even remembered any of that stuff. Faz-baz, quoth I; when I was growing up in the Sixties and Seventies, everyone knew who Larry Storch was.

My saxophone is broken, Larry said. He was taking it to Sam Ash. So he peeled off a block or two later, while I said goodbye (after memorizing his telephone number from the tag).

Then I went around bragging—harrumph, harrumph—that I had just met Larry Storch. At least I bragged for a little while, until I discovered what Larry Storch himself already knew full well: almost no one remembers Larry Storch.

Larry Olivier for Polaroid

No one at my workplace, anyway. At first this was a real shocker. But I soon discovered that no one at Wine & Dine had ever heard of Ida Lupino or Laurence Harvey either. Briefly I considered enlightening them—Surely you remember this movie or that television program?—but I censored that idea as a bridge to nowhere. There’s a scene in Saturday Night Fever where Karen Lynn Gorney tries to impress John Travolta by saying Sir Laurence Olivier came into the office where she works. Hilarity ensues. Travolta doesn’t know who Laurence Olivier is. The girl makes a bad situation worse by explaining that Laurence Olivier is the old guy in the Polaroid commercial on TV. And so Travolta says something like, “Oh, great, maybe he can get you a free camera.”

Fun couple.

The real capper came when I read in the newspaper that Michael Batterberry had died. I’d known Michael Batterberry and his wife Ariane back when I worked in restaurant marketing at American Express, but what I did not know was that Michael was the founder of Wine & Dine magazine. It’s a fantastic story, actually. Michael didn’t just conceive it, he began it as an insert in Playboy magazine called, “The International Review” of such-and-such.

This was back in the days when there were very few gourmet magazines or foodie TV shows. (Julia Child was such a curiosity she got on the cover of TIME magazine.) Michael nurtured this venture for a year or two, shortened the title, and finally sold it to this big publisher.

I related this history during our morning “scrum” at Wine & Dine, and got blank stares. Even our online-publishing vice president at Midtown Magazines had never heard of Michael Batterberry.

I faced up to reality. Nobody at Wine & Dine knew anything about the business they worked for. Or much of anything else. Or cared.

Ignorance and apathy were hardly unique to this magazine, of course. Anyway my mind had plenty of other oddities to idle upon.

Ignorance and apathy were hardly unique to this magazine, of course. Anyway my mind had plenty of other oddities to idle upon.

There were a lot of Oriental girls about. About half of them had distinctly un-Oriental names. Instead of Suzy Wong, you had Suzanne Blanchard. Instead of Annie Cheung, you had Annemarie Jensen. It was most peculiar. And while some of these were married surnames, most were not. Neither were they adoptive; these women were too old to have been part of the Red Chinese Baby Fad and too young to be Korean War Orphans. Clearly they had picked names that were common, Western and easy to spell. (Incidentally, it wasn’t enough for a name to be classic and old-American. Those fine old Virginia names Urquhart and Taliaferro would never make the cut. Too weird and foreign-looking! Lee wouldn’t work either…for somewhat different reasons.)

I had a good guess why these ladies had taken on their simple “American” monikers. It was so their racial background would not scream from the top of the résumé whenever they applied for a job. They weren’t ashamed of their origin or family names; they just wanted the hiring manager’s first reaction to be, Oh look, Catherine Charlton went to Duke, instead of: Oh wow, another Cathy Ching.

There’s a lot of silliness and whimsy in this situation. Everyone noticed the incongruous names, but it seemed verboten to talk about them. Taboos are catnip for me. Humorously, obliquely, I’d say, “Annemarie Jensen! Gosh, my grandmother was a Jensen. I wonder if Annemarie and I are related?” And then I’d smile blandly while everyone else in the room visibly stiffened.

An Appalling Place. I started out in the editorial department of Wine & Dine but since I worked for the online edition, I regularly met with the “developers,” who inhabited a filthy, ill-lit warren two floors above me. It really was a sty, an extreme caricature of a crowded, ugly developers’ space. The techies sat cheek-by-jowl along white melamine countertops about 20″ deep, their noses up close to their monitor and laptop screens. Paper plates, sauce bottles, and other detritus of past lunches littered the window sills and tables. The worn, torn, shredded grey carpeting hadn’t been vacuumed in years. Dead flies and mouse turds occasionally tumbled out of the HVAC vents and ceiling panels.

The developers were mostly slobs, dressed in hoodies and sneakers that should have gone to Goodwill ten years ago. Six Caucasian and two Chinese developers huddled together (side-by-side, back-to-back) between the first pair of counters. Farther back, behind a partition, was Stinky-winky Land. You had East Indians, Pakistanis, and one very raffish, Jewish concert musician and composer who did contractual dev work so he could tour with symphonies when he wanted to, and not have to struggle for gigs at weddings and bar mitzvahs.

The South Asians were mostly there on contract, through an Indian company called Cognizant. Two or three years before I arrived, someone in management was sold on the idea of “offshoring” and “outsourcing” most of our development work, with the result that we had some Indians on site who were there merely to coordinate with the Indians in India, and other Indians on site who did nothing at all but useless make-work projects that were conjured up because our contract with Cognizant had another two years to run and we had to give them something to do.

The South Asians were mostly there on contract, through an Indian company called Cognizant. Two or three years before I arrived, someone in management was sold on the idea of “offshoring” and “outsourcing” most of our development work, with the result that we had some Indians on site who were there merely to coordinate with the Indians in India, and other Indians on site who did nothing at all but useless make-work projects that were conjured up because our contract with Cognizant had another two years to run and we had to give them something to do.

Devland was an appalling place. I thanked my lucky stars that I worked down in Editorial, among normal, hygienic people in ample offices and wide cubicles; where the carpets were clean and plants got watered and mouse turds didn’t tumble from the ceiling. My daily nightmare was that someday, somehow, I might be exiled to the 11th floor, to work amongst this crowd. The likelihood of this seemed remote, up until the very day that I was exiled there.

Devland was an appalling place. I thanked my lucky stars that I worked down in Editorial, among normal, hygienic people in ample offices and wide cubicles; where the carpets were clean and plants got watered and mouse turds didn’t tumble from the ceiling. My daily nightmare was that someday, somehow, I might be exiled to the 11th floor, to work amongst this crowd. The likelihood of this seemed remote, up until the very day that I was exiled there.

The Culture Wars. In the meantime I took in the cultural conflict between the two groups. Down in Online Editorial, the devs were regarded as stubborn, difficult, lazy, and usually out of the office. If you go to the corporate-gossip websites, e.g. Glassdoor.com, you’ll find complaints that the devs need to improve their “work ethic.” Nearly all the devs took Wednesday off. Officially they were “working at home,” but no one in Editorial was fooled. You could e-mail or telephone one of the devs about some emergency on Wednesday, but whatever your problem, it was never going to get fixed till Thursday. Ha ha ha!

Devs made fixes and updates to the Wine & Dine site as seldom as they could. The devs called the updates “sprints,” and initially made them every two weeks. If you wanted to change something on the Wine & Date site, it had to be finished and approved by the Tuesday of the “sprint,” so that it would be “live” on Friday. Editorial complained about this for years, and finally the devs changed to a policy of “continuous enhancement” and “Agile development,” whereby the Wine & Dine website could be updated any day of any week, provided Editorial screamed loudly enough.

Devs made fixes and updates to the Wine & Dine site as seldom as they could. The devs called the updates “sprints,” and initially made them every two weeks. If you wanted to change something on the Wine & Date site, it had to be finished and approved by the Tuesday of the “sprint,” so that it would be “live” on Friday. Editorial complained about this for years, and finally the devs changed to a policy of “continuous enhancement” and “Agile development,” whereby the Wine & Dine website could be updated any day of any week, provided Editorial screamed loudly enough.

When I got kicked upstairs to Devland, I quickly sank into the lazy, slobby mode of the developers, and saw the other side of the argument. The editors and designers were fickle; they always wanted something done right away, and whatever you did for them, it wasn’t enough. You took Wednesday off because by Tuesday evening you needed a goddamned break, for crying out loud. When we declared that no new deployments, no “sprints” could be added on Monday or Friday, it wasn’t to be arbitrary, but to reserve some quiet time for work and testing. We said there could be no discussion meetings between Development and Editorial on Monday, Wednesday, or after 3 on Friday. We laid down these rules out of practicality and principle. Editorial were ditzy and undisciplined.

Editorial didn’t like us, said we were lazy and unhelpful. When the Truth was that Editorial had this nutty notion that all we had to do was Push a Button to work our magic. They didn’t realize how much trouble it was to write new code, and test it, and throw it out, and write it again…

From our filthy perch in Devland we gazed down and judged harshly. The Editorial people were stupid stupid stupid. They knew how to type and go to lunch, and that was about it. They were capricious. Irresponsible.

Your Obedient Servant, the Project Manager. Irresponsible because they couldn’t or wouldn’t take ownership of their own actions. They had these things called “project managers” carry their desires to us. Now, these project managers were nothing like old-fashioned project managers from engineering or construction, with their timelines and Gantt charts. Our project managers were typical of most modern project managers. They were basically clerical, administrative employees who filled many of the same functions that used to be served by low-level supervisors and secretaries (remember secretaries?) Supposedly they communicated the desires of one end of the business (editorial or marketing) with another end (the developers), but their real purpose was to keep the two ends peacefully separated. Relations between the two departments were marked by petulance and mutual suspicion. Editorial felt scorned by Development, and scorned back in return.

Your Obedient Servant, the Project Manager. Irresponsible because they couldn’t or wouldn’t take ownership of their own actions. They had these things called “project managers” carry their desires to us. Now, these project managers were nothing like old-fashioned project managers from engineering or construction, with their timelines and Gantt charts. Our project managers were typical of most modern project managers. They were basically clerical, administrative employees who filled many of the same functions that used to be served by low-level supervisors and secretaries (remember secretaries?) Supposedly they communicated the desires of one end of the business (editorial or marketing) with another end (the developers), but their real purpose was to keep the two ends peacefully separated. Relations between the two departments were marked by petulance and mutual suspicion. Editorial felt scorned by Development, and scorned back in return.

Thus the project manager as referee. The devs habitually thought of the PMs as flunkies of Editorial, but actually the PMs answered to a different department entirely, a cluster of managers with vague responsibilities and even vaguer titles (e.g., Vice President, Digital Content Strategy). Whatever their personal attributes, project managers had the stupidest, least effective roles of all. They weren’t “managers,” they weren’t decision-makers, and they had no real skills. Their job was merely to make noise and send e-mails, and that is how they spent most of their work days.

The folks at Midtown Magazines kicked me upstairs to join Wine & Dine‘s web development team. Boy did I hate that. In Editorial we scorned the Dev group. And now I here I was, one of the scorned.

The folks at Midtown Magazines kicked me upstairs to join Wine & Dine‘s web development team. Boy did I hate that. In Editorial we scorned the Dev group. And now I here I was, one of the scorned.  It Wasn’t All Velvet. I was the only front-end developer in the department; that is, the only person who actually coded webpages for Wine & Dine. (Fly + Buy, our sister publication, had a front-end person, but she got to stay in Editorial. Fly + Buy‘s online editors wouldn’t dream of exiling her to Dev Hell!) There were a couple of other “heads” allotted to front-end development, but they never got filled, so I was constantly doing the work of two or three people.

It Wasn’t All Velvet. I was the only front-end developer in the department; that is, the only person who actually coded webpages for Wine & Dine. (Fly + Buy, our sister publication, had a front-end person, but she got to stay in Editorial. Fly + Buy‘s online editors wouldn’t dream of exiling her to Dev Hell!) There were a couple of other “heads” allotted to front-end development, but they never got filled, so I was constantly doing the work of two or three people. Narwhal traded in our two empty “front-end” heads for a couple of back-end programmers. I do not remember them clearly, but I believe they were mutants from the planet Zod, and that Narwhal had met them through the online-video-game community, or some such. These luminaries lasted six months or a year, par for the course; during which time they coded a little, ate a lot, and played loads of online games and video tutorials.

Narwhal traded in our two empty “front-end” heads for a couple of back-end programmers. I do not remember them clearly, but I believe they were mutants from the planet Zod, and that Narwhal had met them through the online-video-game community, or some such. These luminaries lasted six months or a year, par for the course; during which time they coded a little, ate a lot, and played loads of online games and video tutorials. Meet the Kids.

Meet the Kids. “Glynda,” a Ruby girl, was one or two years out of a small college in Boston, having grown up in Pittsburgh PA and Hopkinton MA. Glynda helped migrate Wine & Dine from its old ColdFusion home to its new Ruby on Rails scaffolding. She was also the expert on our new Rails-based job-tracking system, Redmine. Beyond that she didn’t have much to do, other than some junky work that got tossed her way. She resented it, gritted her teeth over the fact that Devland was always going to be a boys’ club, and moved on out, exactly two years after she arrived. Glynda lived in or near Park Slope, had a corgi dog and a young husband, and a blog. She spent much of her time at work writing her blog. It was called something like, “The Life and Times of a Female Software Engineer.” Had it not been for Glynda, I might never have known that there was anything odd or exceptional about a self-described “female software engineer.” I always assumed that most women avoided devland simply because it’s yucky.

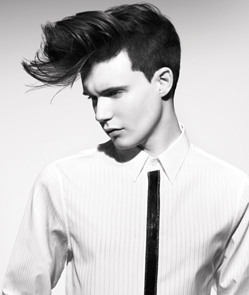

“Glynda,” a Ruby girl, was one or two years out of a small college in Boston, having grown up in Pittsburgh PA and Hopkinton MA. Glynda helped migrate Wine & Dine from its old ColdFusion home to its new Ruby on Rails scaffolding. She was also the expert on our new Rails-based job-tracking system, Redmine. Beyond that she didn’t have much to do, other than some junky work that got tossed her way. She resented it, gritted her teeth over the fact that Devland was always going to be a boys’ club, and moved on out, exactly two years after she arrived. Glynda lived in or near Park Slope, had a corgi dog and a young husband, and a blog. She spent much of her time at work writing her blog. It was called something like, “The Life and Times of a Female Software Engineer.” Had it not been for Glynda, I might never have known that there was anything odd or exceptional about a self-described “female software engineer.” I always assumed that most women avoided devland simply because it’s yucky. Jeremy Preen was in his late 20s, half-Jewish, half-Italian, with recent roots in both Boston and in Brooklyn. Other people might describe Jeremy as a highly narcissistic gay guy, but I wouldn’t. He was just a little over-the-top, like someone who was trying out the role of a narcissistic gay guy. Lots of people try out different acts in their twenties, and when they realize they look silly they can move on and try something else. It’s not like getting a tattoo. Anyway, Jeremy’s act involved spending a lot of care on his high, pointy quiff of hair, which cantilevered out and and curled over his forehead like an awning. He managed somehow always to have exactly three days’ beard-stubble on his face. He dressed year-round in long, pointy-toed shoes, tight black jeans, and (except during summer) a short “bum-freezer” pea-coat. He bore a passing resemblance to the young Laurence Harvey. True to form, he had no idea who Laurence Harvey was.

Jeremy Preen was in his late 20s, half-Jewish, half-Italian, with recent roots in both Boston and in Brooklyn. Other people might describe Jeremy as a highly narcissistic gay guy, but I wouldn’t. He was just a little over-the-top, like someone who was trying out the role of a narcissistic gay guy. Lots of people try out different acts in their twenties, and when they realize they look silly they can move on and try something else. It’s not like getting a tattoo. Anyway, Jeremy’s act involved spending a lot of care on his high, pointy quiff of hair, which cantilevered out and and curled over his forehead like an awning. He managed somehow always to have exactly three days’ beard-stubble on his face. He dressed year-round in long, pointy-toed shoes, tight black jeans, and (except during summer) a short “bum-freezer” pea-coat. He bore a passing resemblance to the young Laurence Harvey. True to form, he had no idea who Laurence Harvey was.

As I noted before, Jeremy’s real métier was office-socializing. It gave him the opportunity to charm people who might be useful to him. (Diametrically different from me; I hate meetings, and the idea of manipulating people or buttering them up makes my skin crawl.) Likewise Jeremy was adept at getting “face time” with anyone who happened to be above him on the totem pole. Jeremy was so good at this, and so persuasive, that he eventually got Narwhal to create a brand-new managerial-level job, just for him. No longer a mere contractor or Marketing coder, Jeremy would now be the UI/UX (User Interface, User Experience) “Channel Manager.” His heavy responsibilities would include holding meetings with the people in Marketing and Editorial, and talking to the outside UI/UX consulting firm that had been engaged to redesign our online magazines.

As I noted before, Jeremy’s real métier was office-socializing. It gave him the opportunity to charm people who might be useful to him. (Diametrically different from me; I hate meetings, and the idea of manipulating people or buttering them up makes my skin crawl.) Likewise Jeremy was adept at getting “face time” with anyone who happened to be above him on the totem pole. Jeremy was so good at this, and so persuasive, that he eventually got Narwhal to create a brand-new managerial-level job, just for him. No longer a mere contractor or Marketing coder, Jeremy would now be the UI/UX (User Interface, User Experience) “Channel Manager.” His heavy responsibilities would include holding meetings with the people in Marketing and Editorial, and talking to the outside UI/UX consulting firm that had been engaged to redesign our online magazines. And so Narwhal was persuaded. He couldn’t stand up to this “diversity” cant. He was himself some kind of nonwhite: negro, red Indian, a touch of something else. Narwhal had been recruited, circus-style, from across the country precisely to fulfill somebody’s wish to have a Person of Color at the department-director level; particularly a P.o.C. like Narwhal, who had a B.S. from Stanford (to which he had no trouble gaining admission, being an in-state, affirmative-action applicant).

And so Narwhal was persuaded. He couldn’t stand up to this “diversity” cant. He was himself some kind of nonwhite: negro, red Indian, a touch of something else. Narwhal had been recruited, circus-style, from across the country precisely to fulfill somebody’s wish to have a Person of Color at the department-director level; particularly a P.o.C. like Narwhal, who had a B.S. from Stanford (to which he had no trouble gaining admission, being an in-state, affirmative-action applicant). (Note: This reads like an overlong draft. I was overwrought and confused when it wrote it in March of 2014. The detail gives a good roadmap of what I thought was in my rear-view mirror, and that is useful to me now, but it probably does not make for pleasant reading. Only now (late summer 2016) do I have an clear perspective on the whole affair.)

(Note: This reads like an overlong draft. I was overwrought and confused when it wrote it in March of 2014. The detail gives a good roadmap of what I thought was in my rear-view mirror, and that is useful to me now, but it probably does not make for pleasant reading. Only now (late summer 2016) do I have an clear perspective on the whole affair.) We had often gone out in groups for lunch: sometimes the whole mob of us, over to Shake Shack, or Szechuan Gourmet, or something Turkish or Japanese, or maybe Maoz, the strange vegan falafel place (Russ was a vegetarian). All this stopped when we moved to 16. We became a chilly little department.

We had often gone out in groups for lunch: sometimes the whole mob of us, over to Shake Shack, or Szechuan Gourmet, or something Turkish or Japanese, or maybe Maoz, the strange vegan falafel place (Russ was a vegetarian). All this stopped when we moved to 16. We became a chilly little department. Our new neighbors were not delighted with us. Many of them were old-fashioned corporate “lifers” who had been in place ten, fifteen, twenty years; the sort of people who bring meticulously prepared lunches from home, arranged in Tupperware containers and soft-fabric lunch-caddies that fill up all the shelf space in the tiny office fridge. The coffee pantry was a cramped little space to begin with, and now here we were doubling the local population. For some reason the pantry housed a fax machine, a laser printer, and a bin for the document shredder, in addition to vending machines for snacks and soft drinks and Fresh Direct “gourmet” lunches ($$$, as Tim Zagat would say); besides the little refrigerator, sink, coffee contraption, cabinets, and a single, tiny microwave oven. No more than three people could fit into the remaining space at the same time.

Our new neighbors were not delighted with us. Many of them were old-fashioned corporate “lifers” who had been in place ten, fifteen, twenty years; the sort of people who bring meticulously prepared lunches from home, arranged in Tupperware containers and soft-fabric lunch-caddies that fill up all the shelf space in the tiny office fridge. The coffee pantry was a cramped little space to begin with, and now here we were doubling the local population. For some reason the pantry housed a fax machine, a laser printer, and a bin for the document shredder, in addition to vending machines for snacks and soft drinks and Fresh Direct “gourmet” lunches ($$$, as Tim Zagat would say); besides the little refrigerator, sink, coffee contraption, cabinets, and a single, tiny microwave oven. No more than three people could fit into the remaining space at the same time.

They took turns with Helen, who was now two. Sometimes Russ took her to work. Bibulous had a very nice creche, and only two other toddlers on hand, so she was more than welcome. Sometimes Nina took Helen to the genetics lab, where they experimented on her. That’s a joke, son. Lots of young ‘uns at the genetics lab, you bet, and loads of toys. Scientists always have the best toys, don’t they? Never mind the price, ma, it’s Science! The baby sometimes got left with a babysitter, but not too often, because half the time Russ or Nina or both of them worked from home.

They took turns with Helen, who was now two. Sometimes Russ took her to work. Bibulous had a very nice creche, and only two other toddlers on hand, so she was more than welcome. Sometimes Nina took Helen to the genetics lab, where they experimented on her. That’s a joke, son. Lots of young ‘uns at the genetics lab, you bet, and loads of toys. Scientists always have the best toys, don’t they? Never mind the price, ma, it’s Science! The baby sometimes got left with a babysitter, but not too often, because half the time Russ or Nina or both of them worked from home. The Spook Who Sat by the Door. The first people to complain were the magazine editors. Their initial peeve was that Devland wasn’t giving them adequate support and hand-holding. Translated, this meant was that Russ was no longer around as their friendly, low-key, go-to contact. During those long months when Online Development didn’t have a director, Russ had functioned as de facto head, despite the fact that he was a mere programmer who had been there for only a year. To make the situation seem less incongruous, the higher-ups bumped Russ up to a “manager” level, bypassing a couple of devs who’d been there five years or more. After Narwhal finally moved in as director, and the editors pretty much ignored him for the first year. By the time they finally got to know Narwhal, we were headed into a slow-motion train-wreck.

The Spook Who Sat by the Door. The first people to complain were the magazine editors. Their initial peeve was that Devland wasn’t giving them adequate support and hand-holding. Translated, this meant was that Russ was no longer around as their friendly, low-key, go-to contact. During those long months when Online Development didn’t have a director, Russ had functioned as de facto head, despite the fact that he was a mere programmer who had been there for only a year. To make the situation seem less incongruous, the higher-ups bumped Russ up to a “manager” level, bypassing a couple of devs who’d been there five years or more. After Narwhal finally moved in as director, and the editors pretty much ignored him for the first year. By the time they finally got to know Narwhal, we were headed into a slow-motion train-wreck. One of Narwhal’s recruits from the video-game-boy world insisted we change our database for Wine & Dine, so we did so, right around the same time that we were migrating our servers and revising the basic design of the online magazine. This completely broke the “versioning” in Wine & Dine‘s CMS (content management system). So if editors rewrote an article, saved it, and then decided to revert to the earlier version, they suddenly found they couldn’t. The earlier versions still lived somewhere out in space, but there was no way to bring them back and reedit them them. Which defeats the whole purpose of having a CMS.

One of Narwhal’s recruits from the video-game-boy world insisted we change our database for Wine & Dine, so we did so, right around the same time that we were migrating our servers and revising the basic design of the online magazine. This completely broke the “versioning” in Wine & Dine‘s CMS (content management system). So if editors rewrote an article, saved it, and then decided to revert to the earlier version, they suddenly found they couldn’t. The earlier versions still lived somewhere out in space, but there was no way to bring them back and reedit them them. Which defeats the whole purpose of having a CMS.

One, two, three developers quit; rats off the foundering vessel. Jeremy and Narwhal scoured the four corners of the Third World for second-rate replacements. As neither Jeremy nor Narwhal had managerial experience (or much corporate background of any kind) they didn’t know how to hire people. Instead of looking for capable team members with the right personalities, they targeted narrow, granular, specific “skills.” We ended up with newcomers who couldn’t communicate very well, although each one was ostensibly the master of some bright and shiny new techno-fad. “Bugalu knows Backbone.js!” Jeremy trilled about one of them. Maybe Bugalu did. Alas, we had no particular need for Backbone.js at that moment, and anyway, as things turned out Bugalu didn’t know much else. These new hires were treated much like the old East Indians from Cognizant: each was put on some specific narrow-gauge project, and then left to work and rework and re-rework it for months on end; while meantime a dwindling number of regular employees tried to hold the hold the magazine sites together.

One, two, three developers quit; rats off the foundering vessel. Jeremy and Narwhal scoured the four corners of the Third World for second-rate replacements. As neither Jeremy nor Narwhal had managerial experience (or much corporate background of any kind) they didn’t know how to hire people. Instead of looking for capable team members with the right personalities, they targeted narrow, granular, specific “skills.” We ended up with newcomers who couldn’t communicate very well, although each one was ostensibly the master of some bright and shiny new techno-fad. “Bugalu knows Backbone.js!” Jeremy trilled about one of them. Maybe Bugalu did. Alas, we had no particular need for Backbone.js at that moment, and anyway, as things turned out Bugalu didn’t know much else. These new hires were treated much like the old East Indians from Cognizant: each was put on some specific narrow-gauge project, and then left to work and rework and re-rework it for months on end; while meantime a dwindling number of regular employees tried to hold the hold the magazine sites together.

As this campaign gathered steam, my co-worker Glynda, the only other female developer, gave her two weeks’ notice. She had had quite enough of Jeremy, Narwhal and company. When Jeremy first took over, he told us that we should pick a developer’s conference to go to, and the department would pay for it. However, when Jeremy and Narwhal and their video-game-boy friends went to South By Southwest in Austin, that expense ate up more than the entire conference budget for the year. So no conferences for the girls.

As this campaign gathered steam, my co-worker Glynda, the only other female developer, gave her two weeks’ notice. She had had quite enough of Jeremy, Narwhal and company. When Jeremy first took over, he told us that we should pick a developer’s conference to go to, and the department would pay for it. However, when Jeremy and Narwhal and their video-game-boy friends went to South By Southwest in Austin, that expense ate up more than the entire conference budget for the year. So no conferences for the girls. Smackdown at Gregory’s. Jeremy went off to Europe for the very first time in his life in July 2012, using the $5000 travel voucher he’d won by cheating on the video contest. When he got back, Narwhal told him to put the screws on me ever harder, to make me quit or explode and be fired. One morning in mid-July they came by my cubicle and demanded I accompany them to a nearby coffeeshop.

Smackdown at Gregory’s. Jeremy went off to Europe for the very first time in his life in July 2012, using the $5000 travel voucher he’d won by cheating on the video contest. When he got back, Narwhal told him to put the screws on me ever harder, to make me quit or explode and be fired. One morning in mid-July they came by my cubicle and demanded I accompany them to a nearby coffeeshop. I tried to complain to HR. There really wasn’t anyone HR to complain to. I’d known a couple of chubby blond girls there, but now they were gone and my own department’s needs were being addressed by a couple of chuckleheaded black women. They both had weird, forgettable names, so I thought of them as

I tried to complain to HR. There really wasn’t anyone HR to complain to. I’d known a couple of chubby blond girls there, but now they were gone and my own department’s needs were being addressed by a couple of chuckleheaded black women. They both had weird, forgettable names, so I thought of them as

This was the outer limit of weirdness. Here were people proposing to flog English fish and chips to the legions of Arthur Treacher fans. How many Arthur Treacher fans were there? Twelve? A hundred?

This was the outer limit of weirdness. Here were people proposing to flog English fish and chips to the legions of Arthur Treacher fans. How many Arthur Treacher fans were there? Twelve? A hundred? The joke was on me, of course. Of all those fast-food start-ups in 1968, Arthur Treacher’s was far and away the most successful. It’s still around—unlike Roy Rogers, Gino’s, Junior Hot Shoppes, Burger Chef, and a hundred other chains extant in the 1960s.

The joke was on me, of course. Of all those fast-food start-ups in 1968, Arthur Treacher’s was far and away the most successful. It’s still around—unlike Roy Rogers, Gino’s, Junior Hot Shoppes, Burger Chef, and a hundred other chains extant in the 1960s.