Archives

Reprise: The Great Impostor (2010)

Preserved from an old blog.

To the Algonquin for a lunch in the Round Table Room today. A dinky little place, the Algonquin, full of dinky undistinguished-looking people, but that is part of its appeal. My event today was a literary MeetUp group that a rotund little lady put together in impromptu fashion, mainly by contacting her Twitter pals. I’m not sure how I got on her list. Anyway, there were 60 or 70 of us, mostly women, mostly Caucasian, mostly middle-aged. Arriving just before luncheon was served, I got put at one of the outlier tables, boasting several younger-than-average people and two women of color, one of them in a wheelchair.

For the main course we could choose between mustard salmon en croûte and chicken paillard. Most people had the salmon. It wasn’t that great.

This is what it’s like when you get old, I guess, I remarked to the young publishing bunny on my left. Lunch with lots of women and hardly any men.

That’s the publishing world, she cheerfully replied. Mostly women. (Is this because it doesn’t pay for shit, or because it’s so femmed up that any male in publishing feels he should be a fag?)

One of the published authors at the table was a lady diesel engineer who has piloted both a tugboat and riverboat. She definitely had the most interesting story to tell, though like a tugboat her tale was modest in size and kept close to home. The one male at the table kept urging her to read a really ripping book he’d picked up recently. Life on the Mississippi, by Mr. Mark Twain. Tugboat Annie made a note.

Me. I explained I did a little copyediting for Penguin Putnam, but that paid little under the best of circumstances, so mostly I worked in ad agencies as a Flash developer. Amazingly, most of my companions seemed to know what that was. So I warmed to the theme: I am the world’s worst Flash developer! Yes, ladies and gent. I get jobs and then lose them when my employers discover my incompetence. This usually takes a few weeks. Fortunately there are many many ad agencies doing pharma Flash development, and they can’t afford to be too picky.

The colored woman in the wheelchair and the PR bunny were wide-eyed at my brazenness. How do you get away with it? Don’t they test you or anything when you start?

Test! Who has time to test? Ha ha! You know, this is a pretty good idea for a book!

And they all agreed that yes indeed it was.

Posted: April 22nd, 2010 under Tests, The Idiots I Deal With.

Protected: Talking Points for Sam

The Philosophical Comedy

Somehow I kept reading or hearing about Heidegger, and when I hear the name Heidegger I always think of Heisenberg. And that started the ball rolling:

There is a high-school philosophy teacher who is given to cyclical mood swings. The condition is one of those affective disorders in the bipolar family. Except instead of having only two or three bad episodes in his life, he gets these wild, lurching manias and crashes every year or two. One of these days he’s going to kill himself. He just knows it. A parent and an uncle committed suicide. It runs in the family, as with the Hemingways.

But he’s got a couple kids and wants to provide for his family. He watches Breaking Bad and sees a parallel, but since he’s not a chemist he can’t make a fortune manufacturing blue meth. What can he do? He decides that the only get-rich-quick scheme he can come up is to create a quasi-religious cult, something that specifically preys on the rich and wayward, like Scientology. Except because he’s a philosopher he can spin his cult as a New School of Philosophy rather than a religion.

He remains in the background, very private. Almost no one’s ever met him. That’s part of the attraction. Nobody knows his real name, they just know he travels under the handle, Heidegger.

This is a shaggy-dog story, I’ll grant you, but the basic premise could be the skeletal plot set-up for a nice satire or farce. Something like Nightmare Alley, except the guy’s afraid of his next mood-swing instead of fearing that he’ll end up as a circus geek.

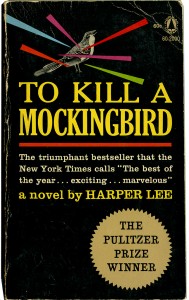

Y’all Can Kill That Mockingbird Now

(Original version of a piece that has since been published elsewhere. As predicted, the subject died a year or two later.)

One of these days Harper Lee is going to kick off and have great big posthumous laugh at our expense. Bwah-hah-hah! Because right there in her Last Notes and Testament, we will find an answer to that puzzlement that has troubled the publishing biz for a half-century or more.

Namely, why didn’t Harper Lee write any more novels after To Kill a Mockingbird?

And the main reason she didn’t, she will aver in words that are coarse and pithy, is that To Kill a Mockingbird was a phoney-baloney contrived piece of fluff. It wasn’t her novel anymore, not after her agent and editors got through tarting it up, to make it modern and popular and sellable. They mutilated her baby, and young Nelle Harper Lee didn’t have the heart to go through that again.

And the main reason she didn’t, she will aver in words that are coarse and pithy, is that To Kill a Mockingbird was a phoney-baloney contrived piece of fluff. It wasn’t her novel anymore, not after her agent and editors got through tarting it up, to make it modern and popular and sellable. They mutilated her baby, and young Nelle Harper Lee didn’t have the heart to go through that again.

Popular and sellable it certainly was. It was on the bestseller list for about two years, and thanks to the sponsorship of Gregory Peck it became a guaranteed hit movie even before a screenplay was written.

And it was modern. By laying on themes of racial strife and civil rights, and deleting most references to Thirties pop-culture, the publishers made the novel as up-to-date and relevant as the latest issue of Look magazine. The book contains some vague references to the New Deal, and a courtroom trial is said to be happening in 1935; officially we’re in the mid-30s for most of the action. But otherwise the setting might as well be the Deep South of the 1950s and even 60s.

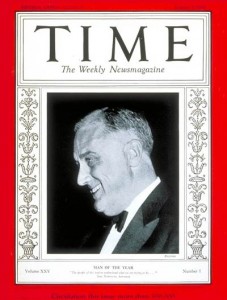

It’s a very peculiar 1930s Alabama that the author conjures up. She doesn’t tell us about seeing Popeye or Shirley Temple or Clark Gable down at the picture show, or reading Beatrice Fairfax or Fontaine Fox in the Mobile Register. In fact, no news at all leaks in from the outside world via radio, cinema, magazines or newspapers. Not a word of Huey Long, the Dust Bowl, Dillinger, League of Nations, Abyssinia, Spain. We are told that our narrator, “Scout,” has been reading since infancy, but she doesn’t seem to read much, not even the Time magazine that her family supposedly gets. International events intrude exactly once, in a painful, smarmy passage in which Scout’s third-grade teacher lectures the class about—what do you suppose? Hitler and the Jews! (Perhaps the teacher does read Time.)

It’s a very peculiar 1930s Alabama that the author conjures up. She doesn’t tell us about seeing Popeye or Shirley Temple or Clark Gable down at the picture show, or reading Beatrice Fairfax or Fontaine Fox in the Mobile Register. In fact, no news at all leaks in from the outside world via radio, cinema, magazines or newspapers. Not a word of Huey Long, the Dust Bowl, Dillinger, League of Nations, Abyssinia, Spain. We are told that our narrator, “Scout,” has been reading since infancy, but she doesn’t seem to read much, not even the Time magazine that her family supposedly gets. International events intrude exactly once, in a painful, smarmy passage in which Scout’s third-grade teacher lectures the class about—what do you suppose? Hitler and the Jews! (Perhaps the teacher does read Time.)

The published novel is very different from Lee’s original typescript. That was a set of loosely linked stories about long summers and oddball neighbors in small-town Alabama. Many of these episodes and character studies are retained in the final product, and they are small, perfect jewels—Boo Radley, the mad recluse; Dill, the narcissistic “pocket Merlin”; Mrs. Dubose, the raging, morphine-addicted Civil War widow; Scout’s snobbish, self-centered cousins who live down on Finch’s Landing.

The novel anticipated the media depiction of the Deep South in the 1960s, and very likely influenced it. Above, the iconic photograph of Sheriff Rainey of Neshoba County, Mississippi, from a December 1964 issue of Life.

This authentic nostalgia is the To Kill a Mockingbird that people fell in love with. However, while these tales still occupy two-thirds of the published book, none of them had sufficient drive or development to carry a major plot. And they were not quite serious, grown-up fiction. “I think for a child’s book it does all right,” Flannery O’Connor wrote a friend around the time the novel won the Pulitzer Prize. And indeed it always has been basically a kiddie story, except for one racy subplot that Lee’s editors grafted onto it. That is the interracial-rape case that dominates much of the second half of the book. Curiously, people who never read the novel, or who mainly remember the Gregory Peck movie, often imagine that this criminal case is the central story, even though it takes up little more than a quarter of the book. (Note: In my HarperPerennial paperback edition of 323 pages, the trial and related events begin at page 164 and end on 259.)

The rape plot is hokum, but the editors and agent who forced it upon Lee knew what they were doing: it ties together many of Lee’s plot strands and characters, and it bumps her wistful recollections up to the grown-up shelf, repositioning it as middlebrow fiction with contemporary (1960) social relevance.

Tastes change. Today the rape plot is laughable, mawkish, stuffed with symbolism. The accused negro, Tom Robinson, has a withered right arm that got mangled years ago when it got caught in a cotton gin. The rapee, Miss Mayella Ewell, comes from a family who are not merely poor white trash from the wrong edge of town, they seem to be illiterate as well. Her father is a murderous drunk, possibly incestuous, who survives by poaching. Her brother Burris is crawling with lice. They are so awful, the story tips over into kind of Tobacco Road black-comedy whenever a Ewell appears. (Thankfully Mayella does not have a harelip.)

Who was the real Tom Robinson? There is a notion prevalent among some schoolteachers and media writers that the Tom Robinson case was loosely based on similar cases in the Deep South during the 1930s. This stems from the vague impression that thousands, or at least hundreds, of innocent negroes were prosecuted and lynched during this era because of White Supremacism and the Ku Klux Klan, and all that nasty bother. According to this school of thinking, Tom Robinson is a composite victim of race prejudice.

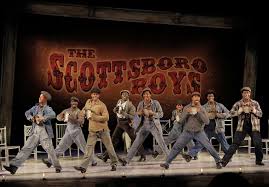

In reality there were very few cases like this. The only notable one in the Deep South that involved interracial fornication with a member of the po-white-trash set was the so-called Scottsboro Boys case. In this saga, we have two young white women who get caught riding railroad boxcars while dressed in overalls. They tell the police they were raped by a gang of black youths also aboard the train. In a protracted series of trials, several of the black youths are convicted of rape and sentenced to long prison terms.

The case was highly publicized in the 1930s, and has never faded from media consciousness, providing fodder in recent years for books, documentaries, and even a Broadway musical. Today the Scottsboro Boys are often spoken of as innocents, martyrs to bigotry and the backward, violent South. The story is put about that the two young women were not only low-class, they were casual prostitutes, and probably deserved what they got, if they really were gang-raped; and anyway, their word shouldn’t be trusted. It’s all their fault.

Scottsboro is frequently cited as the basic template for the rape case in To Kill a Mockingbird. But the resemblance is superficial at best. None of the Scottsboro Boys were hardworking, crippled, husband-and-fathers. In TKAM, nobody suggests Miss Mayella Ewell is a prostitute, or that she deserves to be sexually abused.

The Emmett Till Era. If he wasn’t a Scottsboro Boy, who else could Tom Robinson be? How’s about Emmett Till? This is a theory that scholar-critic Patrick Chura came up with in his penetrating analysis of the novel (Southern Literary Journal, Spring 2000). Chura began by pointing out that the novel has a poor grasp on Thirties history. The WPA shows up two years before the agency was created. And the book’s social attitudes don’t reflect the 1930s at all, rather they seem to echo preoccupations of the 1950s.

Chura rejects the whole Scottsboro theory and says the real prototype for the TKAM rape case was the story of Emmett Till. Emmett Till was a husky, 14-going-on-15 black youth from Chicago who went down to visit his cousins in rural Mississippi in 1955. He made a sexual approach to the young white proprietess of a country store. A couple of nights afterwards Till was beaten to death by the woman’s husband and brother-in-law because he wouldn’t apologize for his behavior.

Chura finds some minor parallels between the two cases. Robinson and Till are both slightly disabled (a withered arm, a stutter), the poor whites are first championed by neighbors, then ostracized because of shame and notoriety. And the trial judges and the press clearly sympathize with the cause of the unfortunate negroes. But the argument doesn’t quite make it. The comparisons are just too strained. Having a stutter is not comparable to having a mangled, useless arm. And the basic narrative of Till case is just too different from the novel’s. The novel’s Tom Robinson is passive and meek. Emmett Till was a big-boy showoff from Chicago who went around bragging that he had a white girlfriend. Even his Mississippi cousins thought he was obnoxious and hoped for his comeuppance.

Nevertheless Chura correctly nails the 1950s Zeitgeist of the novel. So it is most peculiar that he overlooks the most notable inter-race rape case of the era, that of Willie McGee. As a news story this went on for ten years (1945-1955). It got headlines, was a leftist and Civil Rights rallying point, and it closely parallels the rape story in To Kill a Mockingbird.

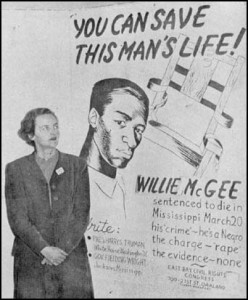

Jessica Mitford and poster, during the CPUSA campaign to protest McGee’s execution. “His ‘crime’ — he’s a Negro.” This sloganeering found echoes in the published version of To Kill a Mockingbird.

Me and Willie McGee. McGee was a black man convicted of raping a (young, attractive, middle-class) white woman in Mississippi in 1945. His lawyers repeatedly appealed, and the appeals were shot down. The case reached a crescendo around 1950, when McGee was due for the electric chair. After a postponement, he was finally executed in May 1951.

The Willie McGee case was a pet cause of the Communist Party USA, through a front organization called the Civil Rights Congress. Now, the CPUSA had been taking a real public-relations beating since about 1945, thanks to Soviet atrocities, the enslavement of eastern Europe, the loss of China, the Alger Hiss case, etc., etc. So now the Party was trying to reposition itself as a kind of charitable, public-spirited organization: a progressive force in favor of Civil Rights and Justice for the Negro. And Willie McGee was an ideal poster child.

In early 1951, as the execution date grew nearer, the Communists came up with a clever retelling of the McGee tale. It was not a simple interracial rape case, they claimed. Willie did not rape that white woman, Mrs. Willette Hawkins; actually Mrs. Hawkins and McGee had been lovers for years! Then Willie wanted to break it off, so the white woman shouted rape to punish him.

Thus sprach the Daily Worker, the CPUSA newspaper. It was a pretty dubious tale to begin with. The McGee case had been going through appeals for five years, yet somehow no one had ever mentioned this long-term “romance” before. But McGee’s new defense team had a wonderfully daffy explanation for this omission: it seems Willie’s original lawyers kept the affair hidden because they thought it would hurt the case, this being Mississippi. (Those all-white juries, you know, with their prejudiced attitudes and all: they might give our Willie something even worse than the electric chair!)

The Party even trotted out a colored woman named Rosalee to tour the country in their dog-and-pony show, telling the world that she was Willie McGee’s wife (she wasn’t) and denouncing Mrs. Hawkins as the white-trash slattern who “raped my husband.”

The Daily Worker kept burnishing its fictional tale of Willie’s romantic entanglement even after he went to the chair. By this point Mrs. Hawkins had heard about it and sued for libel. Finally, in 1955, the Commies admitted they had no evidence. They’d made the whole thing up. The Daily Worker printed retractions and paid a small award for damages.

By that point the Party didn’t care. Willie McGee was long dead, and the story had served its purpose. It had made Willie into a martyr to race prejudice (something we must fight, comrade). Long after most people forgot the details of the case, they’d remember vaguely that Willie McGee was possibly innocent, and executed in a legal lynching.

Because that’s how propaganda works. People don’t remember the logical integrity of arguments. What lingers is the emotional impression. It didn’t matter in the long run whether Willie McGee was guilty or innocent, so long as those “progressive” people who fought for him (e.g., future Congresswoman Bella Abzug) appeared to be on the side of truth and justice.

And there you have it. The tale of Willie McGee, as told in the Daily Worker, was the template for Tom Robinson.

A Parthian Shot. Now, this brings us to Harper Lee’s other big secret about To Kill a Mockingbird. Besides asking why she didn’t write another novel, people routinely asked her which particular racial case of the Deep South she based her rape case upon. She gave vague, dismissive answers, implying that it was a composite of several cases. She never identified any specific case, and no one ever thought to ask her about Willie McGee. After all, McGee was from the 1940s and 50s, not 30s; and anyway, McGee was probably guilty. Therefore, so was the fictional Tom.

And there are even worse complications. If you say Tom Robinson is guilty, then that wise paterfamilias Atticus Finch emerges as one very sleazy lawyer. He does not merely provide competent defense for Tom Robinson, he gratuitously defames the poor girl Mayella Ewell. With no real evidence at hand, he weaves a tale in which she lusted after a crippled black man, and seduced him into fornication. It’s a hair-raising, lurid tale, but it is completely unnecessary. As a fictional device it symbolically shifts the guilt from Tom Robinson to Mayella, but it adds nothing to Tom’s defense case. The jury and townspeople are not really concerned with the issue of consensual vs forcible sex, or whether this person lusted after that one. The two givens in the case are that penetration took place, and that it was interracial. For the men in the jury box, that last bit is the real offense.

Atticus knows they’re not going to acquit his client, so he makes up an unpleasant tale about Mayella, all the while feigning pity for the pathetic lass. But it’s all invention and false sentiment, just like the fantasies that the Daily Worker conjured up about Willette Hawkins and Willie McGee.

Notes and References:

Patrick Chura compares novel to the Emmett Till saga in the Southern Literary Journal.

Alex Heard, author of The Eyes of Willie McGee, blogs about the McGee case.

Washington Post review 2010.

Notes on Bella Abzug and the Civil Rights Congress.

Mockingbird: A Portrait of Harper Lee, by Charles J. Shields, 2006, is particularly good on the shaping of the TKAM phenomenon, both book and movie.

Felicia Day, Last of the Chirpers

If you don’t know who Felicia Day is, you are probably over twenty years in age, and/or spend fewer than ten hours per day on the Inter-Webs.

So, for you underprivileged minds: Felicia Day is a minor actress in her early 30s who has appeared in a couple of TV shows and feature films, as well as some internet-based video dramas that supposedly were very popular with people who like that sort of thing. She is originally from Huntsville, Alabama (which doesn’t mean anything at all, as we all know), went to University of Texas in Austin (ditto) and now lives in or around Los Angeles. She has dark red hair, helped along with various artificial colorings. Six months ago she cut it from waist-length to pixie-bob, which deeply distressed some of her male fans (because what’s the point of being a girl if you’re going to have boy-length hair?). But her current claim to fame is that she does a lot of self-produced, professional-looking videos, and they’re all over YouTube.

When you get to see her, you’ll notice that her persona is highly artificial. I suspect Felicia does not fully realize this. She is a late-model chirper, too young to remember the pre-chirper era, and as no one has yet written a book about chirpers and chirper-culture, she has no reference text to consult. Even Wikipedia lacks an article on chirpers. Therefore she is left with the vague presumption that youngish women have always spoken in chirpy voices and ended every statement on a rising tone, as though it were an inquiry.

When you get to see her, you’ll notice that her persona is highly artificial. I suspect Felicia does not fully realize this. She is a late-model chirper, too young to remember the pre-chirper era, and as no one has yet written a book about chirpers and chirper-culture, she has no reference text to consult. Even Wikipedia lacks an article on chirpers. Therefore she is left with the vague presumption that youngish women have always spoken in chirpy voices and ended every statement on a rising tone, as though it were an inquiry.

Felicia doesn’t remember the early chirpers from the 70s and early 80s, mainly lower-middle-class frails who went around saying things like “ehhww” and “grody to the max,” generally uttered in a register one or two levels higher than their natural speaking voices. The first persons to notice the chirper phenomenon (without giving it a name) were male homosexuals of the ribbon-clerk caste, e.g., retail associates at Bullock’s or Bonwit’s. They took note because half their coworkers were women of the chirper class, and these young gals were so unlike those distaff titans of the silver screen whom these boys always professed to adore. (Lauren Bacall, Bette Davis, Joan Crawford, Ida Lupino, Lizabeth Scott …they never chirped!)

Then Frank Zappa and his daughter Moon Unit made a novelty record about this vocal style in 1982 (Valley Girl), and thereafter the weird locutions were widely acknowledged, although they became known as “Valley Speak,” despite the fact that they were not unique to the San Fernando Valley and they probably didn’t even originate there.

Girls grew up hearing a lot of chirper-speak in the 80s and 90s, so by 2000 you actually had young women in the aspiring professional class talking like this. I remember being astonished in 1998 when I met a new 22-year-old analyst at Salomon Smith Barney. Tiffany, let’s call her, had just emerged from Penn, and yet her speech was extreme chirperese. It was hard not to think it was all a put-on.

Perhaps Tiffany had Bad Companions during her adolescent years, I considered. Or it could just be that she was Jewish; Jews have a noticeable predilection toward the most extreme versions of accents—e.g., Chicago, Brooklyn, London. They affect accents as camouflage, but often overdo it. It’s like you’re wearing cammie fatigues but they’re printed in day-glo colors.

I could think up a dozen other reasons, but a few years later I wouldn’t have have bothered. Tiffany the Chirper may have been a rara avis in the investment banking set in 1998, but by 2005 her locutions were the going thing.

Greta Brawner: no chirper she.

Pay attention when you see a youngish female professor, writer, or lawyer being interviewed on television. If she’s between 25 and 40, there is a high likelihood she is a chirper. The main exceptions to this rule are women who are trained news presenters, for chirping cannot coexist with gravitas. One of the most attractive women on television is Greta Wodele Brawner of C-SPAN’s Washington Journal, and Greta is a thoroughgoing non-chirper. She talks the way most American women did thirty years ago.

Actresses, by and large, are also exceptions, because theatrical people are required to be hyper-aware of their speech and self-presentation. An actress who chirped would be doing so intentionally, trying to stay “in character.” This is what makes Felicia Day such a curiosity. Most of the time she plays a character called Felicia Day, a stripped-down, reconstituted caricature of her own self, and this character is a chirper. It’s a character similar to dramatic roles she’s had on TV (Buffy the Vampire Slayer) and internet comedies, but considering that she’s playing a character with her own name, this chirrupy chirper is just a little too much. It’s annoyingly unclear where the character ends and the real Felicia Day begins. It’s as though Larry David were to play the Larry David character in Curb Your Enthusiasm as a broad impersonation of his earlier avatar, George Costanza on the Seinfeld program.

Which brings me back to my earlier intuition. Felicia Day doesn’t really know she’s chirping. She has typecast herself, locked herself into a comic turn. It’s been suitable for internet videos aimed at millennials, but it’s about to become a liability. The chirper act is on the way out; fads of mannerism have a half-life of about twenty years. You don’t encounter “wild and crazy guys” anymore, or “peace-and-love” hippies; not without a heavy helping of irony or nostalgia, anyway. Females in their teens and early twenties do not chirp anymore, not the ones I meet, anyway. Very soon, anyone who talks and acts like Felicia Day will be presumed to be doing a teenage-girl riff from 1993.

Which brings me back to my earlier intuition. Felicia Day doesn’t really know she’s chirping. She has typecast herself, locked herself into a comic turn. It’s been suitable for internet videos aimed at millennials, but it’s about to become a liability. The chirper act is on the way out; fads of mannerism have a half-life of about twenty years. You don’t encounter “wild and crazy guys” anymore, or “peace-and-love” hippies; not without a heavy helping of irony or nostalgia, anyway. Females in their teens and early twenties do not chirp anymore, not the ones I meet, anyway. Very soon, anyone who talks and acts like Felicia Day will be presumed to be doing a teenage-girl riff from 1993.

It’s been easy for her to hold onto the chirper persona because those vocal memes became so commonplace that many people ceased to notice them. You could be a chirper and still be respectable (though perhaps too lightweight to anchor the nightly news). Chirpers are no longer confused with Valley Girls, they don’t say “gag me with a spoon.” Their mannerisms are not regarded as hopelessly low-class and ugly. But as the fad fades away, people will forget there were respectable chirpers. The legacy of movies and TV shows will inform us all that chirping was mainly characteristic of ditzy, not-too-bright teenage girls in the closing decades of the 20th century.

It’s like the Model T. Say “Model T” to most people, and they think of a rattletrap flivver from about 1910. But T’s were produced until 1927 and the last few designs, particularly the two-seater coupes, were cute and stylish. Nice to be seen in and fun to tool around the campus in. People in the 1920s and 30s knew this, remembered this. But then the first-hand memories faded and we were fed endless media images of the early flivvers and old Henry Ford driving his first production model around Dearborn. The nice Model T’s were forgotten, and we only have the silly ones in our mental slideshow.

It’s like the Model T. Say “Model T” to most people, and they think of a rattletrap flivver from about 1910. But T’s were produced until 1927 and the last few designs, particularly the two-seater coupes, were cute and stylish. Nice to be seen in and fun to tool around the campus in. People in the 1920s and 30s knew this, remembered this. But then the first-hand memories faded and we were fed endless media images of the early flivvers and old Henry Ford driving his first production model around Dearborn. The nice Model T’s were forgotten, and we only have the silly ones in our mental slideshow.

Profound Musings About Chick-Fil-A

(Adapted from a Facebook comment. I have never eaten at one of these franchises, beyond testing out their minimal concession at the NYU snack shoppe.)

Chick-Fil-A must be the worst fast-food franchise name choice since Mahalia Jackson’s Dirty Rice. Unattractive, unmemorable, and a puzzle to pronounce. (Is it CHIK filla? Chick File-Uh? Chick File-Ay?)

But I have very poor judgment in fast-food matters. Back in August 1968, when still in rompers (too hot for the dog days, to be sure) I liked to flip through the classified ad pages of the WSJ and marvel at all the preposterous new chains being floated. In case you don’t remember, fast-food chains were the dot-coms of the late 60s.

The sorriest proposition I saw was something called Arthur Treacher’s Fish & Chips, advertised with a 6-column-inch display ad in the classifieds, showing a portrait of Arthur Treacher himself.

This was the outer limit of weirdness. Here were people proposing to flog English fish and chips to the legions of Arthur Treacher fans. How many Arthur Treacher fans were there? Twelve? A hundred?

This was the outer limit of weirdness. Here were people proposing to flog English fish and chips to the legions of Arthur Treacher fans. How many Arthur Treacher fans were there? Twelve? A hundred?

Arthur Treacher was scarcely a household name. He was mainly recalled (dimly) as a) Jeeves or some other cinematic butler or valet from the late 1930s; b) a supporting character actor in a couple of Shirley Temple films; or, most commonly, as c) Merv Griffin’s sidekick and announcer from the mid-1960s, when Merv has his afternoon talk show from the Little Theatre in Times Square.

There were no Treacher chippies in existence yet. The first few would open in 1969. You could obtain an Arthur Treacher’s Fish & Chips franchise for about $10,000, which I thought was awfully steep, given the marginal appeal of the offering.

The joke was on me, of course. Of all those fast-food start-ups in 1968, Arthur Treacher’s was far and away the most successful. It’s still around—unlike Roy Rogers, Gino’s, Junior Hot Shoppes, Burger Chef, and a hundred other chains extant in the 1960s.

The joke was on me, of course. Of all those fast-food start-ups in 1968, Arthur Treacher’s was far and away the most successful. It’s still around—unlike Roy Rogers, Gino’s, Junior Hot Shoppes, Burger Chef, and a hundred other chains extant in the 1960s.

I think the key point to AT’s survival is that no one else was putting forth a fried-fish chain under the name of a 1930s actor who made his mark playing Jeeves and subalterns. The idea was so far out there that it had no rivals.

And they didn’t sell hamburgers.

Which brings us back to the Chick-Fil-A people. They have a chicken-sandwich chain with an unwieldly, unspellable, essentially unpronounceable name, and nobody else wants to compete. Chick-Fil-A doesn’t have to sell its weird self to everyone; if only 15% of the population knows that Chick-Fil-A is out there, that’s quite enough.

This partly explains Chick-Fil-A’s odd sense of public relations. Most fast-food chains try to steer clear of controversy, but this one likes to stir things up. The company is openly “Christian Conservative,” and they’re not nicey-nicey and hypocritical about it. They don’t open on Sundays, because of course that’s the Lord’s Day. They lose maybe 20% of their possible revenue by being closed on a weekend, but they undoubtedly make much of it back through loyal customers who like that idea, and make a point of going to Chick-Fil-A more often the other six days of the week. (This is speculation on my part; I haven’t seen the numbers.)

And then there are the media flare-ups whenever someone in the company speaks less-than-approvingly of the Homosexual Agenda or Atheistical Humanism or whatever. Inevitably this triggers public denunciations and proposed boycotts of Chick-Fil-A. But most of the boycotters aren’t regular customers anyway. And with the free publicity, Chick-Fil-A starts getting customers it never had before. Most are curiosity-seekers, some are making a political statement, but some are bound to convert into regular customers. Even if that’s only 5%, it’s 5% they didn’t have before, and Chick-Fil-A brought them in without spending a dime on advertising or new signage. All they had to do was keep being mildly eccentric.